Issue #9: The Hierarchy of Money

How Collateral Lubricates the Economy

In a previous issue of Monetary Mechanics, Issue #7, I briefly covered the mechanics of bank reserves and the interactions between the Federal Reserve and the banking system as a whole.

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I will delve more deeply into the nature and function of bank reserves and other more general forms of money, in an attempt to explain why reserves are such an extremely polarizing and contentious topic for many people.

The Hierarchy of Money: The Real Economy

Money is fundamentally hierarchical.1 2 3 Today, most of the time, people are actually referring to bank deposits when talking about money. But what are bank deposits? Bank deposits are a liability of a commercial bank, a derivative claim on the “monetary base,” which consists of physical currency and reserve balances at the central bank. Bank deposits are simply a promise to pay physical currency or to transfer reserve balances on demand (with reserve balances themselves being a promise of the central bank to pay physical currency on demand).

Historically, money has always assumed different forms for different types of transactions and counterparties. Gold served as money between nations, reserve balances served as money between banks, and physical currency served as money between businesses and individuals.4

In the same fashion, bank reserves are a liability of the Federal Reserve and serve as money (i.e. a settlement mechanism) for banks. Banks settle interbank transactions between themselves through various payment networks, such as Fedwire and CHIPS.5 6

In a previous issue of Monetary Mechanics, Issue #8, I covered how commercial banks make new loans and new deposits in the same process at the same time. An important implication of this fact is that money creation = credit creation. This occurs because what is credit to one set of participants at one level of the hierarchy is money to another (a concept I touched on in that issue). Please feel free to review that if you have not yet, as it is very useful for our understanding of this current topic.

Money cannot exist in a vacuum – it must occupy some sort of medium. Like the fish in David Foster Wallace’s parable, we are not usually fully cognizant of the form that money assumes. Hence, the gradual shift away from physical currency signifies not only merely technological implications (i.e. that we send and receive money electronically), but also much more fundamental financial implications (i.e. most transfers of money between individuals and businesses are no longer final settlement, as they are not made with physical currency). What occurs, behind the scenes, of virtually every single transfer of deposits between individuals and businesses is a transfer of reserve balances between the banks involved.7

While this seems like a trivial and meaningless distinction today, the differentiation between bank deposits and physical currency was very important in the not-so-distant past. Indeed, one could pinpoint the Great Depression as the catalyst for the separation of money-like assets (i.e. bank deposits) from money proper (i.e. final settlement in the form of physical currency).8 9 10 Problems with bank deposits, as the intermediate layer of the money hierarchy, have essentially ceased to exist ever since the establishment of the FDIC in 1933 and the creation of deposit insurance against bank accounts.

To summarize, the hierarchy of money in the real economy looks like this:

Bank Reserves – are liabilities of the central bank and money for commercial banks. Reserve balances are still required to settle interbank transactions even though reserve requirements have been eliminated by the Federal Reserve since March 26, 2020.11 Reserve balances at the central bank are the ultimate method of final settlement for transactions that occur between banks (and therefore for the rest of the economy too).

Deposits – are liabilities of commercial banks and money for individuals and businesses. Commercial banks issue new deposits (“broad money”) when they issue new loans. Commercial banks therefore create new broad money ex-nihilo (from nothing) when they extend loans.12 13 14

Physical Currency – plays a special part in the economy as the only method of final settlement (a direct liability of the central bank) that is available and accessible to all participants in the economy (individuals, businesses, and banks).

A settlement can be described as final if there are no other transactions that must occur to extinguish obligations.15 16 17 A transfer of bank deposit funds is not considered as a final settlement because the two participating banks must also transfer bank reserves between each other. A changing of hands of physical currency, however, is considered as a final settlement because there are no other transactions to complete to fulfill obligations by the end of this action.

The Hierarchy of Money: The Financial Economy

All of this is well and good – though only for the participants of the real economy, consisting of individuals and businesses who generally do not need to keep deposit balances much larger than $250,000, the current FDIC insurance limit (other countries have similar limits).

Zoltan Pozsar has this interesting insight regarding the financial system:

The bulk of institutional cash pools are not invested directly in deposits in the traditional banking system but in deposit alternatives primarily in the so-called “shadow” banking system… insured deposit alternatives dominate institutional cash pools’ investment portfolios relative to deposits. The principal reason for this is not search for yield, but search for principal safety and liquidity.18

This happens because keeping uninsured bank deposits in excess of insurance limits is functionally equivalent to lending unsecured to a private counterparty. From a credit risk perspective, lending unsecured to a highly rated sovereign (i.e. buying a T-bill) will always be superior to everything else because the sovereign will never default (in nominal terms). For institutional cash pools, even negative yields on government debt securities are regarded as favorable above all other alternatives, as that is the price paid for safety.19

Thus, if they can avoid it, participants in the financial economy prefer not to hold bank deposits.20 In the financial economy, credit risk-free short-term government securities (i.e. T-bills) serve a role analogous to the monetary base while insured deposit alternatives (i.e. money-market funds and reverse repos) serve a role analogous to bank deposits.21 Consequently, money begins where M2 ends for most of these participants.22

To summarize, the hierarchy of money in the financial economy looks something like this:

Pristine Collateral (C1) – includes securities such as US Treasuries, German Bunds, UK Gilts, Japanese JGBs, and other highly rated, credit risk-free, highly liquid sovereign bonds.23 24

Non-Pristine Collateral (C2) – includes private securitizations such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS), asset-backed securities (ABS), collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), investment-grade corporate debt, high-yield corporate debt, as well as other private securities with questionable rating, credit risk, and liquidity characteristics.25

During booms, the stock of questionable collateral acceptable for use in the collateral system (C2) expands. During busts, certain types of securities have their haircuts raised significantly or are rejected outright for use in the collateral system, causing market participants to crowd into the ultra-safe stock of pristine collateral (C1). In March 2020, this happened in an exaggerated manner, as even off-the-run US Treasuries were rejected as repo collateral due to volatility and liquidity concerns, causing market participants to flock to on-the-run US Treasuries (the safest and most liquid part of C1).26

The demand for insured deposit alternatives in the financial economy is much larger than the outstanding supply of high-quality, credit risk-free, liquid assets acceptable as collateral.27 Thus, just as commercial banks issue deposit liabilities as derivative claims against reserves, “shadow banks” (a.k.a. most financial market participants) issue repo claims against collateral. Typically, high-quality collateral (i.e. C1) is preferred, because it is credit risk-free, is most liquid, and can be used to secure the lowest haircuts.28

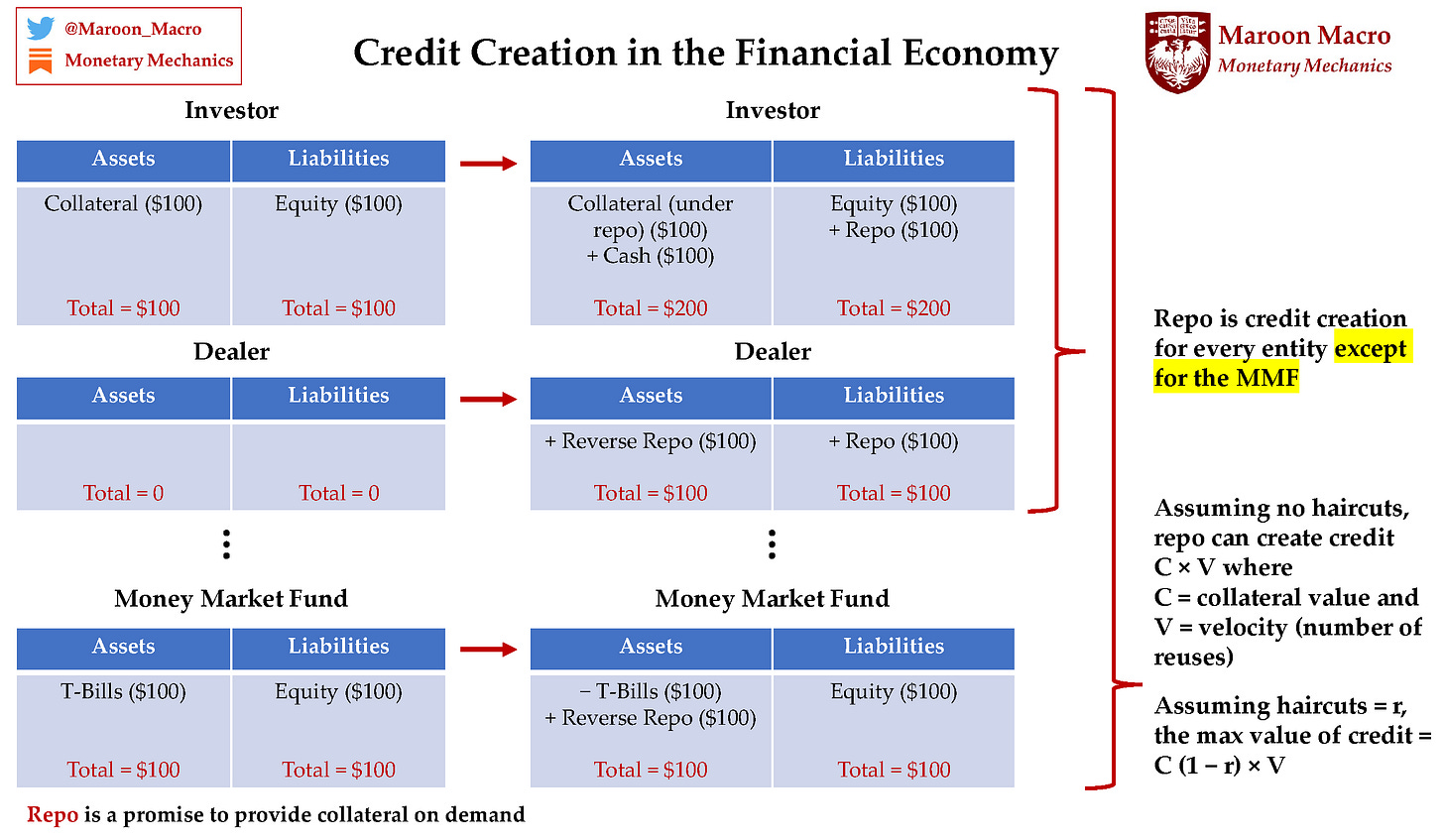

The creation of credit occurs in the financial economy through the creation of repo liabilities against collateral and the circulation of collateral among financial market participants.29 30 Hence, any financial market entity can extend credit to another via the acceptance of a repo claim.31 Consequently, dealers function as intermediaries in the financial economy, in a somewhat similar way to how commercial banks function in the real economy.

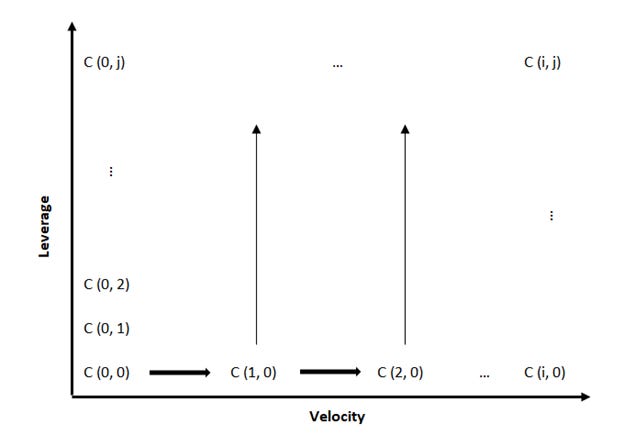

For pristine collateral (C1), haircuts are usually 2-3%. For non-pristine collateral (C2), haircuts range from 5% to 30% or sometimes even higher.32 The haircut is also an implicit measure of the maximum possible amount of leverage that a given financial security can get for a single market participant. For example, if a UST has a 2% haircut, that means that the borrower must put up $2 of equity for every $100 of USTs borrowed. In addition, the implied leverage ratio is the inverse of the haircut. In this example, that is 50x.

Rehypothecation of collateral is the reuse/repledging of collateral by market participants (subject to negotiated limits).33 This engenders something commonly called “collateral velocity” or “collateral chains” – collateral that backs one loan can be employed as collateral to back further loans, so the same underlying asset ends up being able to secure loans worth multiples of its own value.34 35

Together, haircuts and rehypothecation produce a “two-dimensional” money multiplier for collateral, explored in Issue #2 of Monetary Mechanics and illustrated in the figure below.

Hence, deleveraging in the financial system can come from two different areas: increased haircuts (rejection of C2 collateral) or decreased rehypothecation.36 Consequently, while bank reserves are still needed for final settlement in the financial system as a whole, disruptions in collateral supply and redistribution can lead to inelasticity in the payment systems in the intermediate level of the hierarchy of money, especially in the post-Great Depression era.

https://ieor.columbia.edu/files/seasdepts/industrial-engineering-operations-research/pdf-files/Mehrling_P_FESeminar_Sp12-02.pdf

https://www.financialresearch.gov/working-papers/files/OFRwp2014-04_Pozsar_ShadowBankingTheMoneyView.pdf

https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2021/02/Steffen-Murau-GEGI-Study-2-Feb-2021.pdf

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/pdf/research/Working_Paper_412.pdf

https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d105_us.pdf

https://www.frbservices.org/binaries/content/assets/crsocms/resources/rules-regulations/operating-circular-1-accnt-structure.pdf

Read this for further information on this concept: https://fedguy.com/two-tiered-monetary-system/

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/meltzer/whemon92.pdf

https://www.nber.org/reporter/2013number3/banking-crises-and-federal-reserve-lender-last-resort-during-great-depression

https://eh.net/encyclopedia/banking-panics-in-the-us-1873-1933/

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/reservereq.htm

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/quarterly-bulletin/2014/q1/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy

https://www.financialresearch.gov/working-papers/files/OFRwp2014-04_Pozsar_ShadowBankingTheMoneyView_Attachment.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521914001070

https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/files/pf_6.pdf

https://www.newyorkfed.org/aboutthefed/fedpoint/fed43.html

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/epr/12v18n1/1203mart.pdf

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Institutional-Cash-Pools-and-the-Triffin-Dilemma-of-the-U-S-25155

Other reasons include increased demand for unencumbered HQLA resulting from post-crisis regulations including the LCR ratio, initial margin requirements on OTC derivatives, etc. Moreover, negative yielding government securities can still be an attractive investment for a foreign investor depending on the prevailing FX basis.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2014/wp14118.pdf

https://voxeu.org/article/other-deleveraging-what-economists-need-know-about-modern-money-creation-process

https://www.financialresearch.gov/working-papers/files/OFRwp2014-04_Pozsar_ShadowBankingTheMoneyView.pdf

https://www.icmagroup.org/Regulatory-Policy-and-Market-Practice/repo-and-collateral-markets/icma-ercc-publications/frequently-asked-questions-on-repo/6-what-types-of-asset-are-used-as-collateral-in-the-repo-market/

https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs59.pdf

https://www.newyorkfed.org/data-and-statistics/data-visualization/tri-party-repo#interactive/volume

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20200315.htm

https://www.financialresearch.gov/working-papers/files/OFRwp2014-04_Pozsar_ShadowBankingTheMoneyView.pdf

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr740.pdf

https://voxeu.org/article/other-deleveraging-what-economists-need-know-about-modern-money-creation-process

https://voxeu.org/article/global-financial-ecosystem-0

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2232016

https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/inet2012marketfocus_long_shadows.pdf

In this research note, the terms “rehypothecation,” “reuse,” and “repledging” are used interchangeably, even though there are subtle legal distinctions pertaining to differences between “title,” “rights to reuse,” and “ownership.” For our purposes, the differences between these terms are insignificant, so I prefer to use the term “rehypothecation” for clarity, as it is uniquely associated with this practice. In the United States, the SEC’s Rule 15c3a and Regulation T generally limit prime brokers’ use of rehypothecated collateral from a client. Non-US jurisdictions such as UK via English Law do not have any limits. (source: Manmohan Singh, Collateral Markets and Financial Plumbing, 3rd edition, Risk Books, March 19th, 2020).

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Sizable-Role-of-Rehypothecation-in-the-Shadow-Banking-System-24075

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Velocity-of-Pledged-Collateral-Analysis-and-Implications-25332

https://ideas.repec.org/p/imf/imfwpa/2012-179.html

dude, you’re the best … bravo!

Great job men, thanks, I reed you from Argentina.