Issue #7: Quantitative Easing and the Federal Reserve’s Role in the US Treasury Market

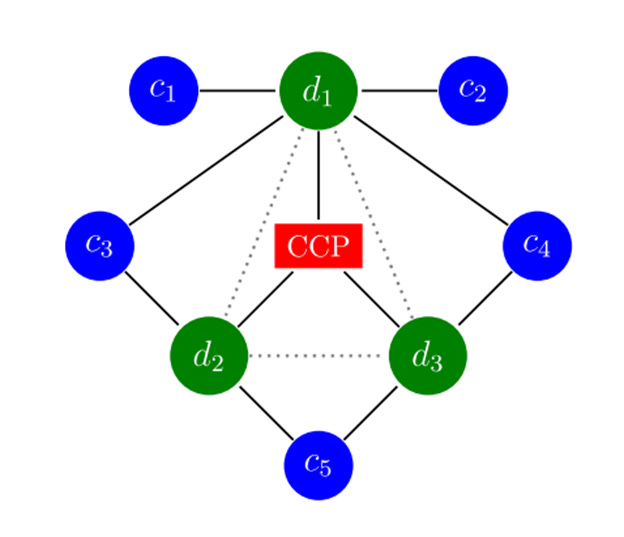

In the last issue of Monetary Mechanics, Issue #6, I covered the structure of the market for US Treasury securities with considerable detail. The diagram below highlights the key components that comprise the US Treasury market, as well as the relationships between them, followed by a brief review, if anyone needs it.

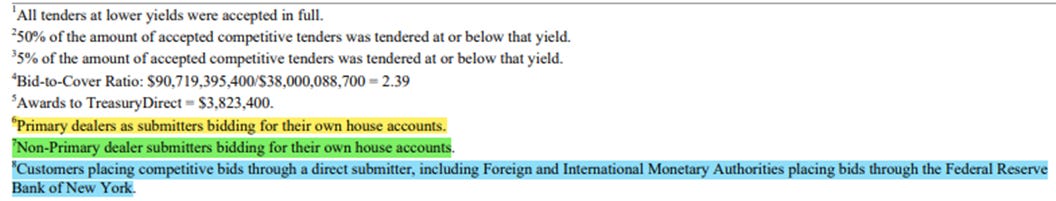

The market for US Treasury securities contains two different segments (the primary market and the secondary market) and auctions off three main classes of securities (bills, notes, and bonds), along with a myriad of other important securities.

The primary market is the market for newly issued “on-the-run” treasury securities. This is the market where the Treasury Department directly sells newly issued bills, notes, and bonds to the investing public. The primary market is also where the Federal Reserve rolls over the maturing portions of its SOMA portfolio.1

Treasury securities initially bought in the primary market at auction can then be sold into the secondary market to a broader class of investors. The secondary market itself has two main segments (the customer-to-dealer segment and the interdealer segment).2

The treasury market, like most of the credit market (as opposed to exchange-traded equities, futures, options, and other financial instruments), trades primarily through dealers who source and warehouse securities to then redistribute them to buy-side clients. These clients rarely (if ever) directly trade with each other. Thus, dealers play an extremely important part in facilitating liquidity in the treasury market, and are one of the reasons that the US treasury market descended into disorder in March 2020.

The diagram above shows a visual schematic of the current treasury market structure. Dealers trade treasuries not only between each other bilaterally but also centrally cleared through a central counterparty (CCP) (i.e. through a “clearinghouse”). Customers trade with dealers and do not trade directly with one another. Estimates deem that approximately 80% of transactions in the treasury market are not cleared by a CCP, unlike exchange-traded derivatives (options, futures, etc.), equities, and a sizable portion of swap-market transactions, all of which are centrally cleared.3 Several officials have noted the possibility of a transition towards mandatory central clearing for all treasury securities as a direct result of the treasury market disruptions in March 2020 – an interesting area we should keep an eye on.4 5

There are two different classes of treasury securities based on their liquidity characteristics (“on-the-run” securities and “off-the-run” securities).6 “On-the-run” securities, as mentioned earlier in relation to the primary market, are the securities most recently released for sale for certain maturities, and are the most actively traded, as well as especially liquid and eligible for the lowest repo haircuts. “Off-the-run” securities, on the other hand, are previously released securities that remain outstanding, which may not be traded regularly. Generally, market prices are discovered in “on-the-run” securities and is assumed to apply to “off-the-run” securities too.

Only a fraction of treasuries of a given maturity is actually trade at a given time, which is one of the important and intrinsic reasons why March 2020 became such a big problem. When foreign central banks and investors began to sell their off-the-run treasuries (which they likely tried to use to secure repo funding first but failed in the process), dealers became backed up and refused to “make markets” or redistribute these treasuries to the broader financial system as a result.

The Federal Reserve and Quantitative Easing

Since treasury securities have a fixed maturity date, billions of dollars’ worth of treasury securities are constantly maturing. Hence, if the Federal Reserve wants to maintain the size of its balance sheet, it must reinvest the proceeds from maturing treasury securities into new treasury issuances. If it does not do that, the size of its balance sheet will naturally decrease as treasuries mature and roll off – this is the definition of “quantitative tightening.”

However, the Federal Reserve does not conduct “quantitative easing,” basically its need to increase its net holdings, in the primary market – that happens in the secondary market instead. If the Fed performed quantitative easing directly in the primary market (i.e. the Fed buying treasuries directly from the treasury, without any other individual’s/institution’s involvement), that would be known as “debt monetization,” which would be the government “borrowing” money from the central bank with no intent to ever pay it back. As a consequence, quantitative easing always maintains one degree of separation, with the private sector acting as an intermediary.

The figure below demonstrates the critical function that the Fed serves in the US treasury market. The Fed not only reinvests the proceeds from maturing treasuries to maintain the size of its balance sheet in the primary market, as mentioned earlier, but also orchestrates “quantitative easing” purchases to increase the net size of its balance sheet via the primary dealers in the secondary market.7

The following discussion is inspired by Joseph Wang’s (a.k.a. @FedGuy) blog post on quantitative easing. If anyone is interested in reading it or needs to reference it, please take a moment to check it out here.

Typically, the simplest and most abridged version of quantitative easing is when a Bank Primary Dealer (i.e. a Primary Dealer that is housed in the same Bank Holding Company as a commercial bank and holds a reserve account at the Fed) sells a UST from its own inventory to the Fed. In this version of quantitative easing, all that happens is a simple asset swap – reserves are swapped for treasuries.

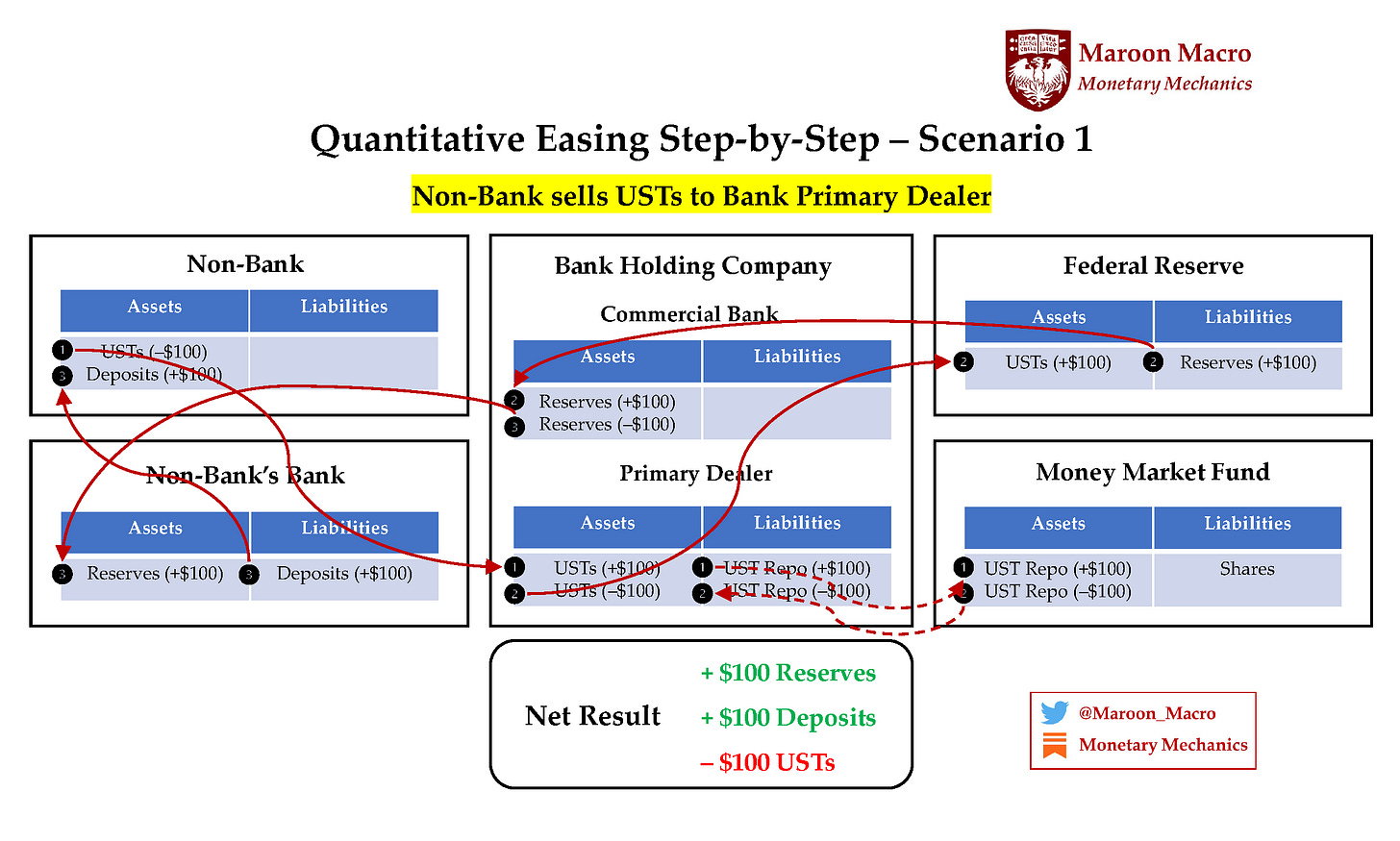

However, when the Fed conducts quantitative easing, the primary dealers take offers from their customers, thus acting as a “conduit” to the Fed, but not as the “ultimate seller” of the UST. In this case, if the ultimate seller is a non-bank that cannot hold reserves (such as an investment fund or pension fund), then bank deposits are created along with bank reserves as a workaround.

Consequently, when the Fed purchases US Treasuries and other securities from the primary dealers during quantitative easing, there are, in a nutshell, four different scenarios that can occur:8

Non-Bank sells USTs to Bank Primary Dealer

Non-Bank sells USTs to Non-Bank Primary Dealer

Bank sells USTs to Bank Primary Dealer

Bank sells USTs to Non-Bank Primary Dealer

Disclaimer: In some of the steps in the diagrams above, I abstract away from some intermediate steps of the deposit creation and destruction process. There are several interpretations on how to account for repo transactions (i.e. asset swap vs. exchange of IOUs), and, for clarity, I choose to ignore deposit transfers in favor of the credit creation interpretation.9

The differentiation between these scenarios is determined by the identity of the “ultimate seller” of the treasury security, as well as by the types of institutions that are allowed to hold reserves at the Fed. Most of these scenarios are very similar, with the only important difference being that extra bank deposits are established when a non-bank is the “ultimate seller” of a US Treasury to the Fed during quantitative easing. This phenomenon occurs because non-banks are not allowed to hold accounts at the Fed and are, as a result, not allowed to hold reserves there too. Hence, the non-bank’s bank must hold the reserves created by the Fed while the non-bank holds the extra bank deposits created to bypass this issue. For anyone who might be interested in learning more about the hierarchy of money, I will cover that topic in future issues of Monetary Mechanics.

Consequently, all of this points to the fact that quantitative easing can theoretically cause an increase in M2. However, it is highly unlikely that these deposits will be actually spent in the real economy – most likely, these deposits will be immediately spent and exchanged for financial assets in a portfolio diversification process (a.k.a. the “portfolio effect”), as non-banks do not want to risk holding large amounts of these deposits (if it is avoidable), since standard FDIC insurance coverage on bank accounts is limited to $250,000. To do otherwise would be idiocy at best, insanity at worst.

https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/treasury-rollover-faq

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WP62_Duffie_v2.pdf

Ibid.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20210301a.htm

https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2020/log201023

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/o/on-the-runtreasuries.asp

An important note about the Treasury’s transition from on-the-run to off-the-run securities: “A Treasury transitions from on-the-run to off-the-run once a newer set of Treasuries is released for sale. For example, if one-year Treasury notes are issued today, those would be the current on-the-run Treasuries. If another set of Treasury notes get issued in the next month, those become the new on-the-run Treasuries, and the previously issued Treasuries are considered off-the-run. This cycle continues as each new batch is created, with every group other than the newest run deemed off-the-run for the rest of its associated time, until it is cashed in upon reaching maturity.”

https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/treasury-reinvestments-purchases-faq

https://fedguy.com/quantitative-easing-step-by-step/

https://privatedebtproject.org/pdp/cmsb/uploads/murau-pforr-private-debt-project-final.pdf

Hi,

You mention in the post that there are a few “deposit creation” steps that are skipped in the QE examples above. Just to make sure I’m clear, do these refer to the deposits technically created by the sale of UST to the Fed for the PD’s account (whether it’s under a BHC or not)?

If it is solely a PD-Fed trade, deposits will be created for the PD’s account at its bank (whether under a BHC or not). If it is a MMF-PD-Fed trade, then the PD will still be left with “new” deposits, right?

Lastly, to be clear, in a MMF-PD-Fed trade, QE expands MMF bank’s balance sheet, holds PD’s bank balance sheet neutral, and expands Fed balance sheet (last one is obvious).