Issue #8: The Origins and Evolution of the Modern Monetary System

Part 1: "Asset Management" – The Classic Model of Banking (Deposit-Taking and Lending)

To better understand and assess the modern monetary system, it is helpful to review the financial innovation and development that transformed banks from (relatively) simple institutions that took deposits and made loans into the complex institutions that they are today.1

There are a few financial innovations that are of paramount importance:

Liability Management (a.k.a. “wholesale finance”) – the expansion of banking strategy that transformed banks from passive acceptors of deposits to aggressive operators in the money market. This includes federal funds borrowing/lending, repo, commercial paper, money market funds, eurocurrency/eurodollar banking, and much more.

Securitization (a.k.a. “market-based finance”) – the disintermediation of traditional commercial bank lending in favor of bonds and the pooling of illiquid, untradeable loans to form liquid, tradable securities. This includes the proliferation of mortgage-backed securities, high-yield bonds, increased IG corporate bond issuance vs. loans, and other asset-backed securitizations. This also coincided with the advent of the pension system, which indirectly funneled America’s future retirement savings into the financial market.

OTC Derivatives and Value-at-Risk (VaR) – combined with Basel risk-weightings, these innovations introduced increasingly esoteric and mathematical definitions of “money-ness,” resulting in the redefinition of money as “bank balance sheet capacity.” This also cemented the shift of bank business models towards fee-generating, off-balance sheet banking activity as opposed to maturity transformation based on net interest margin or balance sheet expanding arbitrage.

However, before I further examine and evaluate these rather complex topics, I want to first review the classic model of money and banking.

Prior to the 1960s, the banking system closely approximated the one described by the money (deposit) multiplier. Although commercial banks create new money (deposits) when they lend, they had to make sure that their liabilities (+ equity capital) were adequate to cover their total asset base to avoid being insolvent and being forced into bankruptcy. Moreover, they had to make sure that they had enough reserves, not only to satisfy the reserve requirements against certain types of deposit liabilities, but also to settle interbank transactions.

In a world with only one bank, this would not be a problem, because deposits would only be transferred between accounts at the same bank and would never be taken out of the banking system (except during physical currency management, the amount of which would be trivial).2

This is precisely how central bank reserves work. This is also precisely why the amount of reserves in the banking system, in which banks no longer utilize intraday credit and daylight overdrafts at the Fed, remains stable, outside of temporary or permanent open market operations by the Fed (TOMO/POMO) and physical currency management by banks.3 4 5 6 7

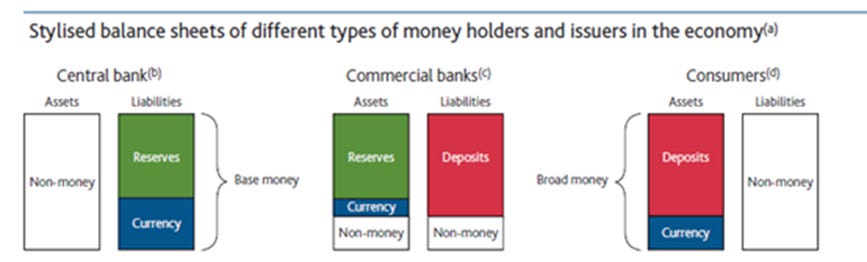

In the real world, however, there are many banks that consumers and businesses can choose among to deposit money with, and it is not guaranteed that the recipient of a loan will choose to keep his or her deposits at the same bank. In the real world, consumers and businesses transfer bank deposits between each other, while banks transfer reserves between each other.

If a customer withdraws the newly created deposits, the bank uses reserves (vault cash or reserve balances) to meet this demand for liquidity. If the customer wishes to transform their deposits into physical currency, then the bank uses its vault cash. If the customer wishes to transfer their deposits over to another bank (“Bank B”), then the customer’s current bank transfers reserve balances over to “Bank B.” Both vault cash and reserve balances can be used to fulfill reserve requirements.8

Since March 2020, the Federal Reserve has eliminated the remaining reserve requirements on banks.9 Before March 2020, reserve requirements were set on certain types of bank liabilities, including net transaction accounts, nonpersonal time deposits, and eurocurrency liabilities. Hence, in the past, financial innovations were largely determined and driven by the types of liabilities that banks were required to hold reserves against.10 11 12 13 14

Reserve balances can only be created by:

Open market operations from the Federal Reserve

Transfers of excess physical vault cash to the Federal Reserve when demand for physical currency decreases

Reserve requirements (before their elimination) can only be fulfilled by:

Reserve balances held directly at a Federal Reserve Bank or indirectly through a correspondent bank

Physical vault cash

When one deposits physical currency at a bank, one receives bank deposits. When a bank deposits physical currency at the Fed, the bank receives bank reserves. Thus, reserves are equivalent to cash.

The diagram below shows a stylized example of the “hierarchy of money” in the real economy.15 I will further cover that topic to greater length and in greater detail in future issues of Monetary Mechanics.

Depository institutions (i.e. banks and credit unions), apart from a few exceptions (e.g. the U.S. Treasury, the GSEs, and FHLBs), are the only entities that can hold reserves. Just the same way that individuals and businesses can hold an account at a bank, with deposits in it, banks themselves can hold an account at the Fed, with reserves in it. However, individuals and businesses cannot directly hold reserves.

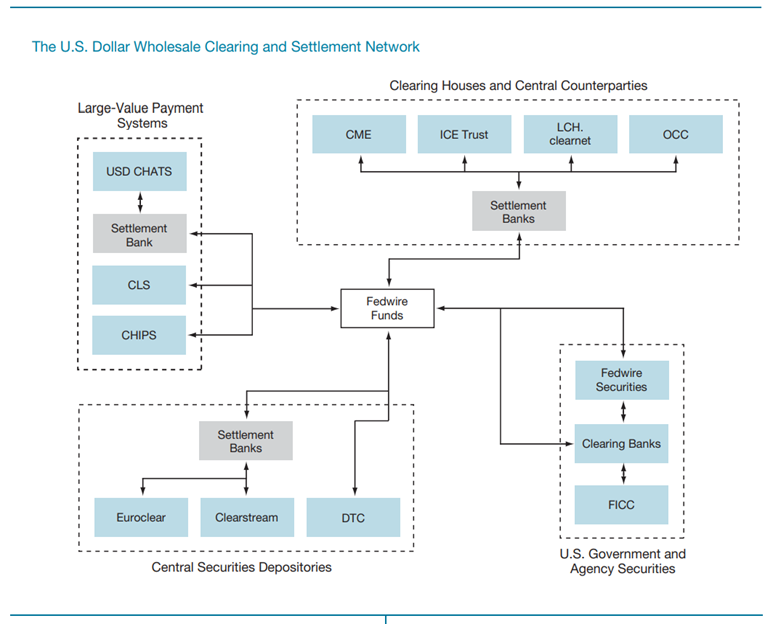

Despite the elimination of reserve requirements, banks still need reserves to make payments via various payment settlement platforms, such as Fedwire and CHIPS.16

A bank would run low on reserves if and when many of that bank’s customers withdraw physical cash or transfer deposits over time. Until about 2010, the bank would settle an issue as such by borrowing reserves from the federal funds market to maintain the proper level of reserves (for settlement and reserve requirement satisfaction purposes). However, in the post-GFC world, domestic banks would rarely, if ever, borrow from the federal funds market, due to the abundance of reserves and the stringency of liquidity requirements.17

Consequently, in a world without reserve borrowing (either from other banks in the Fed Funds market or from the Fed itself with intraday credit and daylight overdrafts), the only way to replenish a reserve deficiency is to attract and attain more deposits.

How Do Reserves Limit Banks?

I cannot stress enough the significance of this topic, as it is one of the main reasons why reserves and their use are so misunderstood.

Reserve requirements provide a limit on individual bank balance sheet expansion (i.e. on money creation) only if reserves cannot be borrowed from other banks in the Federal Funds market or if reserves cannot be borrowed temporarily from the Federal Reserve itself (either through the discount window or through intraday credit and daylight overdraft capability).

Banks are limited to the deposits that they can attain and retain if these two things cannot happen, which then in turn limit the extent to which banks can engage in lending, since the only other way to obtain more reserves is to obtain more deposits.

In such a scenario (a.k.a. a “repressed financial regime”), banks typically adjust the level of their lending (assets) to the amount of deposits at their disposal (liabilities) – an approach known as “asset management.”

Prior to the re-liberalization of finance in the late 1950s, balance sheet management was generally relatively passive on the deposits side. In the past, banks had a steady pool of customary deposits that limited how much their assets were able to expand. The funds were allocated among various activities to ensure appropriate levels of reserves and earning assets.18

However, this all changed with the reemergence of the Federal Funds market, as well as the invention of novel banking practices (e.g. “bidding for deposits”) and types of liabilities (i.e. repo and commercial paper), which enabled banks to expand the sizes of their balance sheets to far above and beyond what was historically available to them. These changes in bank behavior are collectively known as “liability management,” which I will soon cover in the next issue of this installment on the origins and evolution of the modern monetary system.

Pre-WWII era banking was not actually as simple as it is traditionally depicted as being, but that is a topic for another research note. I will focus solely on the transformation of banking since 1945 in this research note.

In practice, prior to the financial crisis, banks made use of intraday credit offered by the Federal Reserve so that the total quantity of reserve balances would fluctuate wildly on any given day due to payment needs in the banking system (reference: Singh and Stella, “Some Alternative Money Facts,” IMF Working Paper, 2020). Furthermore, the Federal Reserve does not set monetary policy by targeting a quantity of bank reserves (or any other monetary aggregate), but by setting the price of bank reserves through open market operations (since the 1970s-80s, even though it was never made explicit when the Fed switched to an interest rate targeting regime). During the course of pre-crisis open market operations, the level of bank reserves would naturally rise and fall due to payment demands.

https://research-doc.credit-suisse.com/docView?language=ENG&format=PDF&sourceid=em&document_id=1081995001&serialid=3Wu3wFUMyBePtRtdFV1OMYgKjlWVo06EvleE1YFXV0o%3D&cspId=1767182447312478208&toolbar=1

https://www.newyorkfed.org/aboutthefed/fedpoint/fed01.html

https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/2015-economic-commentaries/ec-201502-excess-reserves-oceans-of-cash.aspx

http://fedguy.com/what-determines-the-level-of-bank-reserves/

http://www.adriendavernas.com/papers/repomadness.pdf

“The Board's Regulation D (Reserve Requirements of Depository Institutions) provides that reserve requirements must be satisfied by holding vault cash and, if vault cash is insufficient, by maintaining a balance in an account at a Federal Reserve Bank. An institution may hold that balance directly with a Reserve Bank or with another institution in a pass-through relationship. The portion of the reserve requirement not satisfied by vault cash is called the reserve balance requirement. Reserve requirements are imposed on "depository institutions," defined as commercial banks, savings banks, savings and loan associations, credit unions, U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks, Edge corporations, and agreement corporations.” (source: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/reservereq.htm).

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20200315b.htm

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/quarterly_review/1977v2/v2n2article7.pdf

https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/03/03/CyreeGrifWin.pdf

Marcia L. Stigum, The Money Market: Myth, Reality, and Practice, 1978.

Alfred Broaddus, “Financial Innovation in the United States – Background, Current Status and Prospects,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Review January/February 1985.

https://ideas.repec.org/p/cte/whrepe/wp09-10.html

https://ieor.columbia.edu/files/seasdepts/industrial-engineering-operations-research/pdf-files/Mehrling_P_FESeminar_Sp12-02.pdf

https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d105_us.pdf

https://research-doc.credit-suisse.com/docView?language=ENG&format=PDF&sourceid=em&document_id=1083423171&serialid=1y3h1R6Rj58HwGS582KtuMll1d9COkFaBmQQnzoxDAU%3D&cspId=null

T. M. Podoloski, Financial Innovation and the Money Supply, Basil Blackwell, 1986.

... but "Lending in Lockstep" is used by Bank of England and others to agitate against money creation by banks (on the way to CBDCs) - see here further and concrete critics (within description of pics): https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Commercial_Banks_Balance_Sheets_(stylized)_-_Pic-Fusion_comparing_Aggregated_View_to_Single_View_(Pic_Source_Bank_of_England_2014).PNG

Hi,

2018/21 Frank Decker and Charles E. Goodhart described some elements of "credit mechanics" by a group of german economics, especially by Wilhelm Lautenbach. Maybe that could be useful. One of them, Hans Gestrich shows in form of stylized (commercial) bank balance sheets (1936) so called "Lending in Lockstep" (by commercial banks) - see for example: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ed/Kreditgewaehrung_im_Gleichschritt_%28Giralgeldsch%C3%B6pfung%29_Gestrich_1936.png

Thank you, best regards

C.G.BRANDSTETTER