In Issue #1 of Monetary Mechanics, I outlined an abstract overview of the impact of credit to the real economy, arguing that credit extension (especially through bank lending) for the primary purpose of business investment is important for generating future economic growth and typically leads to low and stable inflation as the aggregate purchasing power of the economy grows roughly in line with the production of useful goods and services.

In that issue, I also argued that credit extension for the purpose of consumption is likely to have a disproportionate effect on inflation of several segments of the CPI/PPI/PCE indices, because it increases marginal consumption power but does not directly facilitate investment in the production of useful goods and services.

In this issue, I will attempt to analyze and assess these arguments.

Credit Extension to Businesses in the Real Economy

There are two main ways that businesses can acquire additional financing in order to take advantage of opportunities for growth: debt and equity. Generally, companies prefer to take on debt, rather than issue additional equity, because issuing equity is almost always a more expensive form of financing. Hence, companies usually only issue additional equity if credit markets are unavailable/inaccessible to them.

Large Enterprise Financing

There are a variety of securities that companies can issue that have varying levels of seniority in the capital structure (i.e. likelihoods of getting one’s money back in bankruptcy). However, in this issue, I am only going to focus on the two biggest sources of debt financing: bank lending and bond issuing.

In Issue #13 of Monetary Mechanics, I detailed some of the most important differences and subtleties in bank lending vs. bond issuing, arguing that bank lending is far more likely to have an effect on structural inflation because it increases the aggregate purchasing power of the economy.

On the other hand, bond issuing, while still providing a form of credit and funding for large companies, does not result in money creation because it redistributes, rather than creates, commercial bank deposits. Consequently, bond issuing does not increase the aggregate purchasing power of the economy (i.e. it increases money “velocity” but not money “quantity”). However, it is important to keep in mind that the orthodox definitions of these terms are far too simplistic, which is something that I discussed in further detail in Issue #9 of Monetary Mechanics.

Historically, the financing for large companies was approximately evenly divided between bank loans and corporate bonds. However, after the GFC, loan extension to nonfinancial companies has barely recovered while bond issuance has rocketed. This may be a result of the “reach for yield” amongst fixed income investors, the increased costs of loans for banks resulting from compressed interest rate spreads that are close to the Zero Lower Bound (ZLB), and also post-crisis rules and regulations designed to better prop up banks’ capital and liquidity buffers.1 2

Fundamentally, credit creation via loan extension creates new money in the real economy and takes up bank balance sheet space while credit creation via bond issuance decidedly does not. A loan extension creates new demand deposits. A bond issuance, on the other hand, merely reallocates existing money from investors in the capital markets to the corporate issuer.3 4

We have explained and established that large companies, particularly after the GFC, tend to finance themselves through bond issuance. Now, the question is what are these large companies doing with the proceeds from corporate bond issuance?

Since the GFC, large public companies have significantly increased their shareholder payouts (dividends and share buybacks) relative to their operating income. This implies that a significant portion of this corporate bond issuance is not going to investment in productive enterprises for the future, but instead to payouts to shareholders.

This implies that the public company executives either

believe that there are no projects with a risk-adjusted return on invested capital (ROIC) that is greater than simply returning capital to shareholders (i.e. the public company executives believe that the company has a limited economic future)

or

are returning capital to shareholders due to uneconomic reasons despite the existence/abundance of profitable investment opportunities (i.e. the public company executives are making decisions based on investor sentiment, EPS bonus targets, etc.)

In both scenarios, the long-term viability of such large public companies is suspect.

However, large public companies are not the most important part of the US economy. In fact, it is the national collection of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that produces about half of the private sector GDP, employs about half of the private sector payroll, and also creates two out of three net new jobs.5

Small and Medium Enterprise Financing

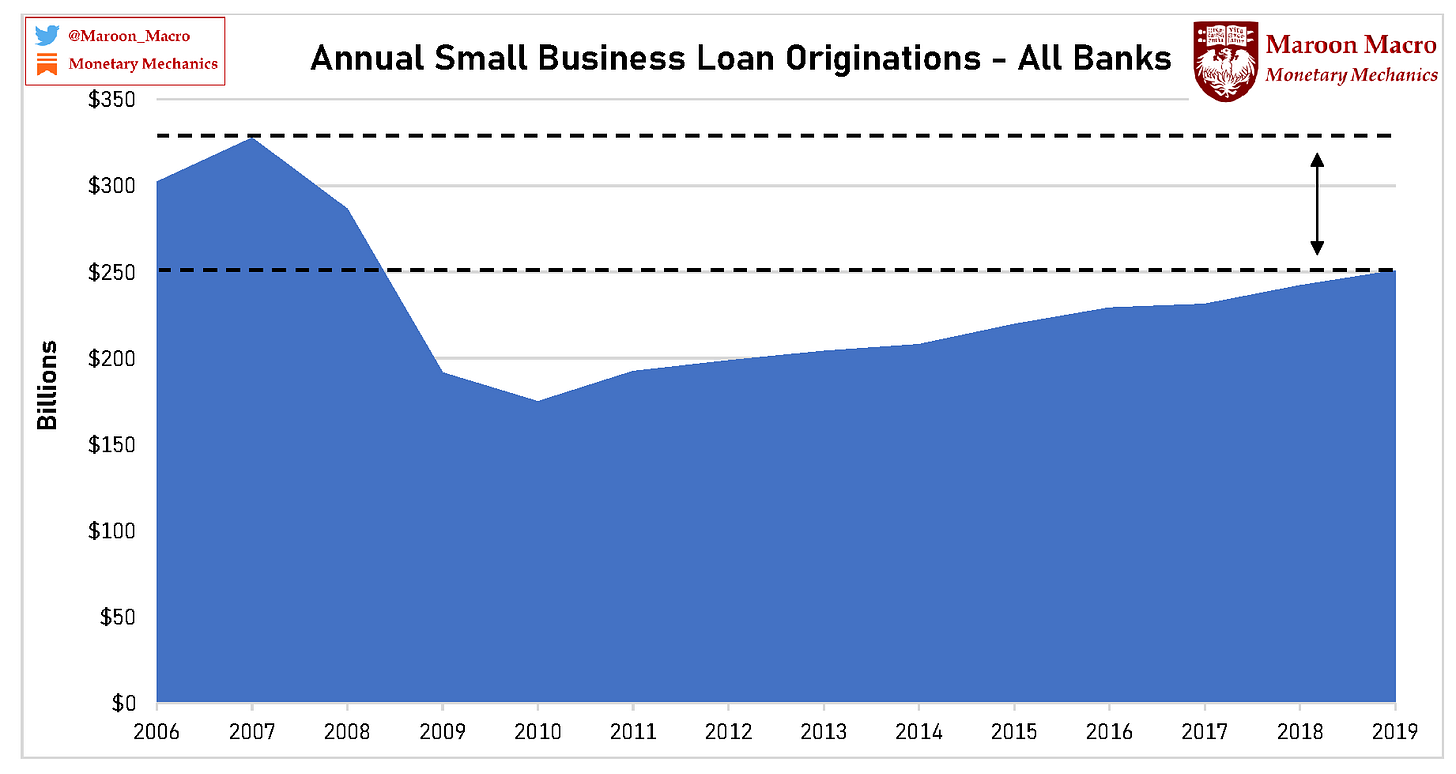

SMEs face far more limited financing options than large public companies. Usually, SMEs can only depend on secured bank loans while large public companies can choose from a menu of options (e.g. equity, secured/unsecured bonds, secured/unsecured bank loans, commercial paper, etc.). Furthermore, ever since the GFC, loan originations to SMEs (defined as commercial bank loans less than $1 million) have cratered and have yet to rise to their pre-crisis level.

Diving a little deeper into the data, we realize that, contrary to popular belief, large banks have been and continue to be a significant source of financing for SMEs.

Before the financial crisis, the top 4 banks accounted for one-third of SME loans and the largest banks (with $50B+ in assets) accounted for more than one-half of SME loans. After the financial crisis, the share of the top 4 banks in SME lending has sharply declined to approximately 23%.6 Since the GFC, the interruption of the flow of credit to SMEs from the largest banks has resulted in increases in interest rates, fewer business creations/expansions, increases in unemployment rates, and decreases in wages. Furthermore, even when the flow of credit to SMEs started to recuperate after 2010 as other lenders slowly filled the void, interest rates have remained elevated and negative effects on wages have persisted (despite the fact that unemployment rates returned to reasonable levels, to about 5-6%, by 2014).7

Importantly, the researchers conclude that “it does not appear that aggregate small business lending conditions were overheated in high Top 4 counties before the crisis.”8 Consequently, the post-crisis decline in credit to SMEs is not a return to the pre-bubble norm, but rather a permanent and alarming break in a previously well-established trend.

The researchers offer some explanations as to why the decline in the flow of credit to SMEs from the largest banks may be overexaggerated:

Another possibility is that the slow rebound was in part a consequence of heightened post-crisis financial regulation. Even as late as 2014, a significant fraction of senior managers’ time at the largest banks was being consumed by the need to comply with the array of heightened regulations that had gone into effect following the crisis – Basel III’s new capital and liquidity rules, the Federal Reserve’s annual bank stress tests, the preparation of so-called “living wills,” to name but a few. This left less bandwidth to devote to the task of reimagining a struggling peripheral business line such as small business lending. More directly, in the wake of the crisis, effective capital requirements have gone up not only in absolute terms, but also by more for the very largest banks… Moreover, the implicit risk weights for small business loans in particular may have increased at large banks in recent years. This would be the case to the extent that the stress-testing regime that the Federal Reserve now applies to banks with assets over $50 billion makes relatively severe assumptions about the losses on small business loans in an economic downturn… Finally, it is possible that Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations may have played a role… KYC compliance costs are incurred when a bank enters into any relationship with a small business, and are not specific to just lending.9

The figure below shows the lingering and long-lasting effect of the decline in large bank credit on real earnings throughout the entire economy.

What is most interesting about these findings is that, contrary to popular belief, large banks have been and may still be a more crucial source of financing for SMEs than community/small banks. Whether it is due to increased risk perception, decreased investment profitability, rules and regulations, or other factors that came into play after the GFC, the final outcome is an unfortunate loss of financing to one of the most critical instruments of innovation and job creation in the economy.

With the knowledge that large banks played a conspicuous part in financing SMEs, it is somewhat safe to say that the collapse in wholesale funding, which large banks disproportionately depend on, contributed to the shrinking of bank balance sheets, which caused the contraction of credit offered to SMEs.

Consumer and Financial Credit

The following statistics and figures approximate the flow of money to the consumer and financial sectors of the economy.

The figure above shows that while the total amount of consumer credit has increased since the GFC, housing debt has stayed almost completely flat since the GFC. The figure below, following up on that, shows that the increase in the total amount of consumer credit since the GFC has come from mostly auto loans, which have increased approximately $0.5 trillion, and student loans, which have increased approximately $1 trillion.

The figure below shows that this mirrors the trend in the issuance of consumer credit asset-backed securities (ABS) in the United States, which has been relatively subdued since the GFC. Though not all consumer credit is packaged into ABS securities for issuance, nonetheless, it connects consumer credit to the financial sector and is illustrative of general credit trends.

The figure below shows the major classes of financial assets in the United States. The total value of the US equity market is measured via the total market value of all the publicly listed companies in the US on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (NASDAQ), or the over-the-counter stock market of OTC Markets Group (OTCQX). The total value of the US credit market is measured via the Federal Reserve’s Financial Accounts of the United States (Z.1) (limited to total debt securities and all sectors). This dataset specifically excludes loans but includes both public and private bonds outstanding. Finally, the total value of the US real estate market is taken from Zillow’s annual study of the total value of the US real estate market.

Summing the values of these together and plotting it against US GDP, we see that the value of total US financial assets vs. US GDP has been steadily increasing since 2011 and has recently surpassed its 2006-2007 record high.

What this implies is that money has been flowing more into the financial economy, bidding up the prices of existing assets in the process, and flowing less into the real economy, into transactions that are actually counted as GDP (i.e. final goods and services).

Similarly, subdued consumer credit growth also accounts for the relative lack of consumer price inflation (as shown in the CPI/PPI/PCE indices) in the past decade, outside of the outliers, with the exception of educational and medical expenses. Evidently, educational expense inflation in the last decade has been driven by federal government guarantees, which have enabled increases in student loan issuances and thus tuition prices too. While the data here does not explain medical expense inflation, there is substantial evidence that medical expense inflation in the last decade has been driven by legislative issues involving the passage of the Affordable Care Act.10 11

https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/A%20Financial%20System.pdf

https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/documents/a-financial-system-capital-markets-final-final.pdf

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf?la=en&hash=9A8788FD44A62D8BB927123544205CE476E01654

https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/finana/v36y2014icp71-77.html

https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/15-004_09b1bf8b-eb2a-4e63-9c4e-0374f770856f.pdf

https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=52458

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Fall2014BPEA_Kowalski.pdf

https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2016/07/28/overwhelming-evidence-that-obamacare-caused-premiums-to-increase-substantially/?sh=4e17515615be

Hi Maroon. Brilliant as usual. I am quite interested on studying seriously Liquidity. I am reading books and newsletter like yours but Do you recommend me further knowledge to interpretet deeply the system? And in order to build my own models or stats? University? Any course or something? Any help would it be really apreciatted. Thanks in advance