Issue #13: What is Inflation?

Recently, there has been a lot of talk about inflation and deflation among central bankers, policymakers, economists, investors, market participants, and even everyday individuals due to the unprecedented events of the past 12-18 months. There has been perhaps no other time, aside from the immediate post-GFC period, when the outlook for inflation has been so uncertain, with such a wide range of views from a variety of respected thinkers. Hence, in this current issue of Monetary Mechanics, I thought it might be timely for me to clarify some fundamental principles, as well as my own framework for thinking, about inflation, which has served me well and allowed me some sense of clarity during very turbulent financial and economic events.

This passage was written in 2009 but still seems highly relevant today:

When we talk to investors, their inflation expectations seem to be remarkably unanchored. To put it bluntly, investors’ inflation expectations seem to be all over the shop, ranging from extreme deflation to hyperinflation, and every shade of grey in between. But, for the majority of them, it is simply that they do not have much confidence in their ability to predict inflation after recent events.1

Historic Fiscal and Monetary Interventions

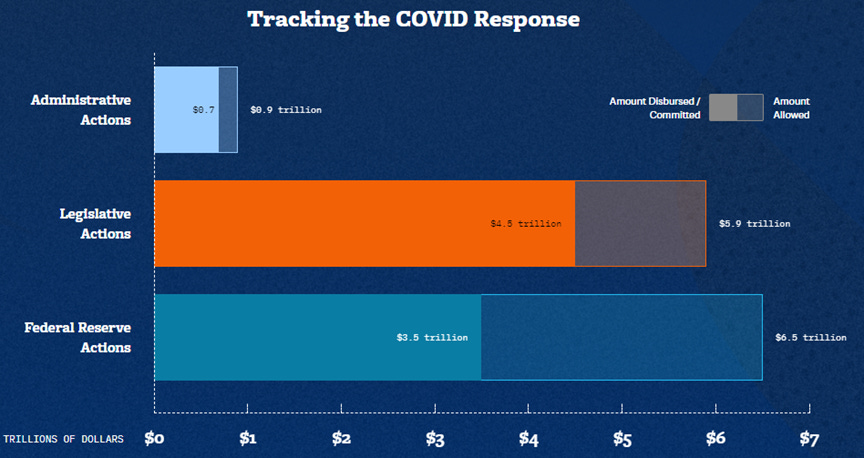

To most analysts, it is inarguable that the combination of recent extreme market events with some of the largest fiscal and monetary interventions in history, as well as the Federal Reserve’s recent switch to “flexible average inflation targeting” (FAIT), seems like a recipe for disaster.

After the GFC, it was thought that several rounds of quantitative easing (QE), totaling nearly $4 trillion, should be sufficient to restore the banking system, as that massively increased the total quantity of reserve balances in the financial system from less than $20 billion to a whopping $2.7 trillion before it decreased to about $1.5 trillion during taper. Naturally, many thought the Federal Reserve had “gone too far” with QE 2/3.

In other issues of Monetary Mechanics, I have covered some important first principles about the nature of bank reserves and the proper functioning of the banking system:

Issue #8: The Origins and Evolution of the Modern Monetary System: Part 1

Issue #11: The Origins and Evolution of the Modern Monetary System: Part 2

I recommend you go back and give them a read (if you have not), and review them again (if you have already), as a basic understanding of these topics will be beneficial going forward and for the following discourse on inflation.

First, we should start by questioning what we mean when we say “inflation.” On the surface, this seems like a trivial question. However, we should be mindful of the fact that inflation is not a monolithic and simple phenomenon.

Here are several popular definitions of inflation:

An increase in a hedonically adjusted and statistical price index such as Consumer Price Index (CPI), Producer Price Index (PPI), and Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE)

When nominal wage increases in excess of productivity

An increase in the prices of financial assets (equities, fixed income, real estate, etc.)

Monetary debasement against real assets (gold, land, other durable goods, etc.)

Traditional Measures of Inflation

Definition 1 is the most important and relevant for traditional discussions about “inflation,” but there have been growing concerns and criticisms that traditional measures of CPI/PPI/PCE, which are based on hedonic price adjustments and other assumptions, understate “true” inflation.2 For those who are unfamiliar with the term, hedonic price adjustments are a method of adjusting prices according to changing product quality as a result of innovation. Basically, if the quality of a product improves, but its market price stays the same, its hedonistically adjusted price decreases (to take into account the changing product quality).3

The substitution effect is also another type of assumption that is made in the calculation processes of CPI/PPI/PCE indices. In doing so, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) assumes that similar goods are substitutable to a certain degree. Basically, if the price of Good A increases while the price of Good B stays the same, the BLS assumes that consumers will substitute more of Good B for Good A, which means that the impact of Good A’s price increase on the overall price index is muted.

There are many problems with these hedonically adjusted and statistical price indices, most or all of which pertain to the fact that they are purported to measure a “cost of living” when in actuality they fail to do so accurately. The main problem is that these price indices, which utilize a litany of assumptions and adjustments in their calculation processes, are, as a result, highly manufactured and synthetic measurements that do not properly track nominal price increases over time.4

Despite the failings and limitations of CPI/PPI/PCE indices, for now, we will assume that these indices can estimate inflation with a reasonable degree of accuracy, as a full evaluation of the merits and demerits of such indices warrants a more detailed debate.

Inflation Expectations

Definition 2 is often blamed for the structural causes behind the Great Inflation during the 1970s due to a phenomenon called “wage-price spirals.”5 6 The basic idea is that “cost-push” inflation arises when workers receive higher wages, which increases their demand for and consumption of goods, which increases the prices of those goods, which results in higher and higher wages, so on and so forth.

This is also the reason behind the strong emphasis that policymakers place on the idea of “inflation expectations.” Since this reflexive feedback loop is driven by individuals’ and businesses’ expectations of future price increases, which can only be controlled by the pristine reputation of central bankers, they believe that they need to stand ready to suppress and squash such inflation should it ever arise.

Non-Traditional Measures of Inflation

Definitions 3 and 4 are non-traditional measures of inflation that are usually espoused by those unsatisfied with traditional inflation price indices (CPI/PPI/PCE). In general, they are used to attempt to explain the absence of inflation seen in these traditional inflation price indices. However, financial asset price inflation is driven by fundamentally different structural factors than broad-based increases in the price level of real goods and services. Financial asset price inflation is driven by the (leveraged) purchase of preexisting assets, and is not the result of sinister monetary debasement, which reduces everybody’s purchasing power in a tangible way.

This is especially evident in housing prices in recent years. Housing prices have been driven up because mortgage lending permits borrowing based on the collateral value of housing prices, so that increases in real estate valuations facilitate more borrowing which facilitates further increases in real estate valuations. This is an asset bubble, not inflation, as mentioned in other issues of Monetary Mechanics. Thus, in the rest of this issue, I will discuss inflation primarily with definitions 1 and 2 in mind.

Monetary vs. Non-Monetary Inflation/Deflation

I want to further differentiate between what I call “monetary driven” inflation/deflation and “non-monetary driven” inflation/deflation.

Monetary driven inflation/deflation is driven by changes in the quantity, velocity, or composition of money and money-like assets, which affects the purchasing power of individuals, businesses, and investors. These changes can be caused by monetary policy conducted by a central bank (e.g. quantitative easing, raising/lowering the federal funds target, etc.). These changes can also be caused by endogenous monetary conditions in the private bank/market centered monetary system (e.g. volume of bond/loan issuance, medium-term/long-term interest rates, haircuts/collateral velocity, etc.). Consequently, monetary driven inflation will most likely show up in traditional measures of inflation, as well as in the prices of financial assets.

Non-monetary driven inflation/deflation is driven by forces not directly related to changes in monetary conditions. An example is legislation or regulation changes that create uneconomic incentive structures and disrupt market forces (e.g. federally guaranteed student loan and mortgage debt, the Affordable Care Act and the general structure of the health insurance industry, etc.). Other examples include temporary shortages of labor or key materials (copper, iron, semiconductors, etc.), technological innovation, demographic shifts, globalization effects, etc. Non-monetary driven inflation tends to impact certain segments of the economy disproportionately compared to others, such as in college tuition, healthcare, electronics, used cars, and lumber. Consequently, non-monetary driven inflation will no doubt show up in certain segments of traditional measures of inflation, but will have less of an impact on traditional headline measures of inflation.

I focus primarily on monetary driven inflation/deflation, as it most directly affects monetary policy and the prices of financial assets and therefore has the potential to have the largest magnitude of effect across the widest swath of the economy.

A final thing to note about non-monetary driven inflation/deflation is that it tends to be either self-extinguishing, brought about by a discrete one-off change, or driven by long-term trends that are unlikely to reverse rapidly. Non-monetary driven inflation/deflation is self-extinguishing when it is caused by temporary demand/supply imbalances, because a new equilibrium is established when consumers eventually run out of purchasing power. The third and final possibility (non-monetary driven inflation/deflation due to technology, demographics, globalization, etc.) is worth keeping an eye on, given recent global political and public health disturbances.

How Bank Balance Sheet Expansion Drives Inflation

As discussed in detail in Issue #1 and Issue #8 of Monetary Mechanics, bank lending is the only means to increase the purchasing power of individuals and businesses since banks are responsible for money creation. Moreover, bank lending is fundamentally distinct from the extension of credit through bond issuance, because bond issuance merely results in the redistribution of preexisting bank deposits and therefore does not result in money creation.7

Although bond issuance can redistribute purchasing power (i.e. “money” in the form of bank deposits), this can only lead to an increase in the purchasing power of businesses at the expense of the purchasing power of investors (and indirectly savers).8 Therefore, banks are the only entity that can cause an increase in purchasing power for one entity without a simultaneous decrease in purchasing power for another entity. This is because bank liabilities (bank deposits) are widely accepted as a means of payment and are regarded as “money” under M1/M2.9 For a deeper understanding of this concept, please review Issue #9 of Monetary Mechanics.

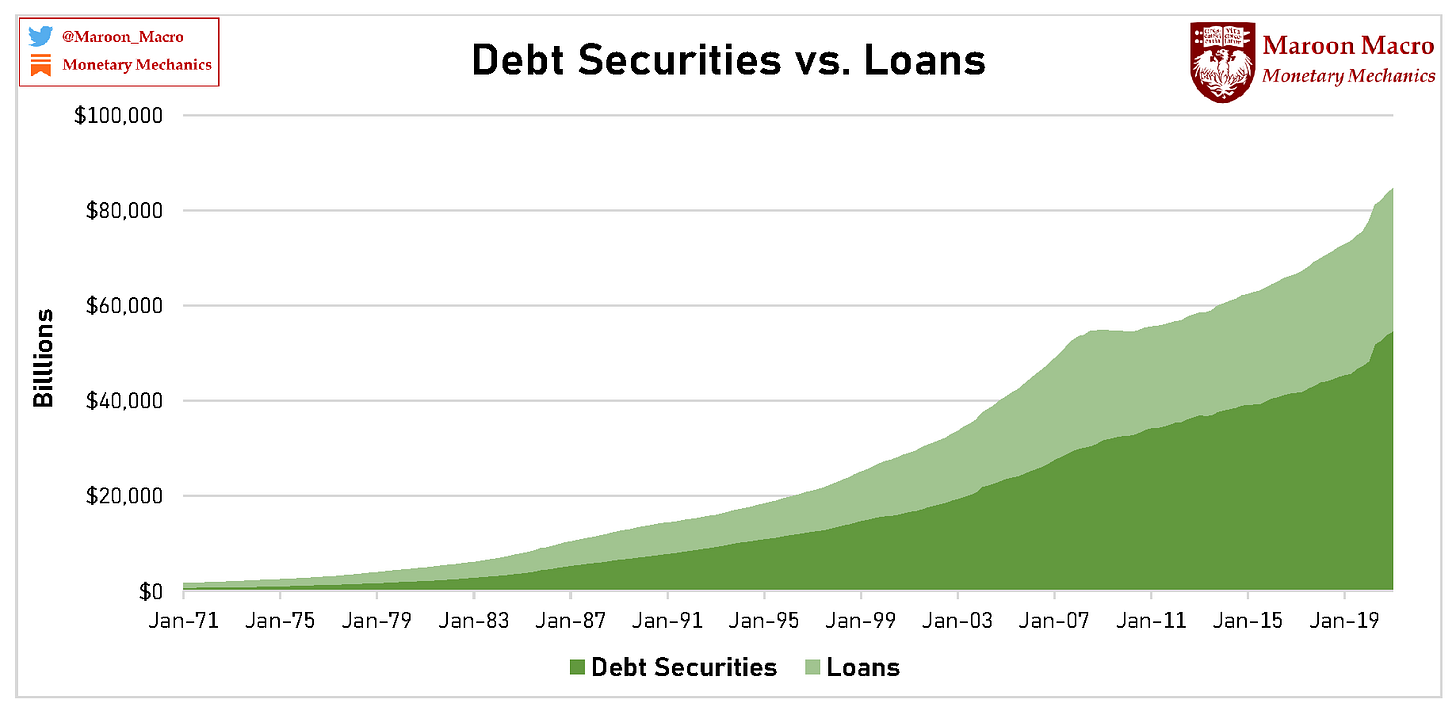

Since the GFC, bond financing has become more popular than bank lending due to the elevated cost of bank lending and low net interest margins.10

Since bond financing reallocates purchasing power while bank lending creates new purchasing power, only bank lending can cause a broad increase in inflation by increasing aggregate purchasing power relative to the stock of useful goods and services. If bank lending is anemic, inflation will also tend to be anemic in the long run, which partially explains why inflation has been so muted in the post-GFC period.

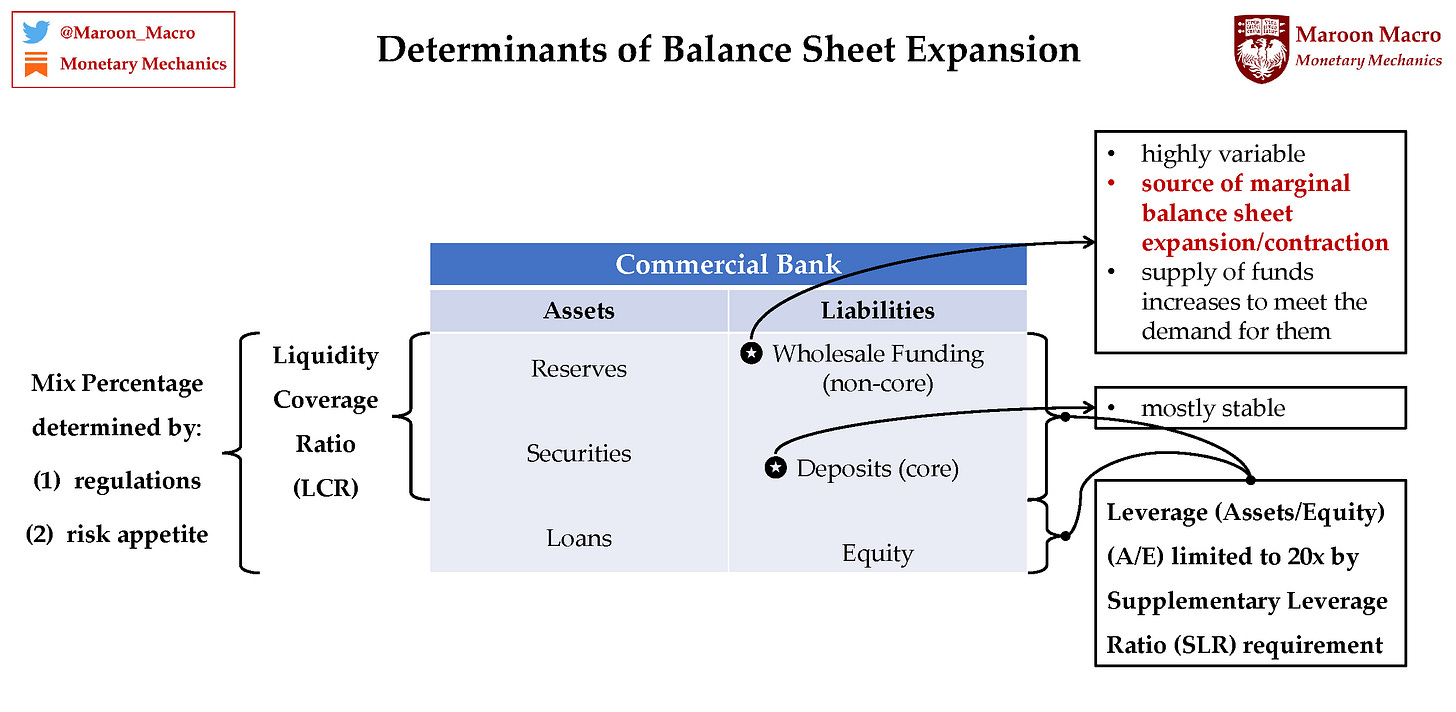

Banks are funding constrained, meaning that they must issue new liabilities (e.g. deposits, CDs, CP, repo, etc.) to fund investments in order to increase their lending activities. The vast majority of banking assets in the US economy are held by the largest banks, which disproportionately depend on short-term wholesale funding (e.g. CDs, CP, repo, interbank loans, etc.).11 12

Since deposits are a relatively stable source of funding, the amount of which is largely out of the control of banks, as they cannot choose who deposits how much with them, banks rely on short-term wholesale funding to meet marginal demand for loans.13

In summary, due to post-crisis changes in legislations, regulations, and bank behavior and the resultant reduced availability of short-term wholesale funding, the banking system is now unable to expand its balance sheet via traditional lending activities in the way that it once did. This essentially puts a cap on the amount of new purchasing power that can be created, which limits inflation potential. Large banks have cultivated “fortress balance sheets” and significant excess liquidity, but that defensiveness is synonymous with risk-aversion, and, in a capitalist market economy, risk-seeking behavior is crucial in creating future inflation and economic growth.

While large public companies can substitute the reduction in bank lending with bond financing, small businesses, which account for 50% of private payroll and 60% of net new job creation, cannot. As a consequence, small businesses have struggled significantly due to the inability/unwillingness of banks to make the smaller dollar loans that small businesses seek, leading to a lingering credit gap.14

In conclusion, with 50% of the private payroll of the real economy crippled due to the reduction in credit through bank lending, as well as with the aggregate purchasing power in the real economy reduced due to the lack of recovery in bank lending after the GFC, it seems unlikely that we will experience sustained monetary inflation.

Jonathan Wilmot and James Sweeney, “Long Shadows: Collateral Money, Asset Bubbles, and Inflation,” Credit Suisse Fixed Income Research, May 5, 2009.

https://www.epsilontheory.com/im-trying-to-understand-hedonic-adjustments/

https://www.bls.gov/cpi/quality-adjustment/questions-and-answers.htm

https://praxisadvisory.com/will-the-real-rate-of-inflation-please-stand-up/

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-inflation

https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/05/03/part2/Meltzer.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521915001477

https://fedguy.com/the-primary-and-secondary-market-for-money/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521914001434

https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/economic-synopses/2013/11/15/bank-vs-bond-financing-over-the-business-cycle/

https://mlc.degroote.mcmaster.ca/files/2018/08/Banks-Funding-Structure-and-Earnings-Quality-August-2018.pdf

https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2018-november-financial-stability-report-funding.htm

https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/03/would-monetary-tightening-increase-bank-wholesale-funding/

https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=51972