Banks are special entities in the real economy due to their ability to create money ex-nihilo (i.e. “from nothing”).1 2 3 4 What this money is created for (lending) and where it flows (spending) has tremendous influence in determining rates of economic growth, consumer price inflation, and financial asset price inflation. In this inaugural issue of Monetary Mechanics, I will focus primarily on the role of how commercial bank lending most directly affects the real economy, as well as completing my analysis by covering the financial economy.

Economists during the 1960s and 1970s experimented with a monetarist approach to enacting monetary policy (i.e. directly targeting the rate of growth of a given monetary aggregate, M1 or M2), with the belief that this was the most effective and efficient method of controlling monetary conditions in the economy. However, they ran into a variety of problems, as their functions for money demand were not stable. Specifically, the economy began using forms of money which did not fall under these economists’ definitions of M1 or M2.5 6

Monetarism is based on the “quantity theory of money” or the idea that MV = PY where M = money supply, V = velocity of money, P = price level, and Y = nominal GDP. V is typically assumed to be constant for simplicity’s sake, since it represents an abstract and difficult to measure idea about the “turnover” of each $1 in the economy.

Milton Friedman’s quantity theory of money built on the work of his monetarist precursor Irving Fisher, whose equation took on a more generalized format: MV = PQ, where Q = quantity of transactions. In Friedman’s more specialized formulation, he implicitly assumes that PY = PQ (i.e. that all transactions are part of GDP).7 8

However, a major problem with this formulation is that not all transactions are part of GDP. Financial transactions (real estate, equities, bonds, etc.) are many times larger than GDP and represent a potential use of funds just as any transaction that is officially counted and included in GDP.9

While we can still say that “total spending” or “money used” = “value of all transactions,” we must disaggregate between financial and real economy transactions.

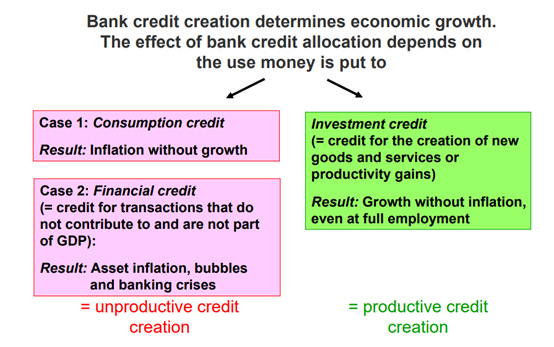

Using this differentiation of “financial” money vs. “real” money, and with the knowledge that banks do in fact create new money when extending loans, we can recognize a few important facts:

Secured lending towards asset purchases (real or financial) leads to asset bubbles because of the feedback loop between money creation and collateral price increases.

The creation of new money to facilitate a purchase ceteris paribus will increase the price of that asset. Moreover, most if not all secured loans use, as the basis for the security of their loans, the collateral value of the underlying asset. Using the example of a mortgage loan, a bank may ensure that its loan only covers a maximum percentage of the total value of the house (“loan-to-value ratio”), so that in the event that the borrower defaults, the bank can seize the house and sell it to recoup its losses.

Secured lending against collateral assets leads to a feedback loop whereby new money is created to purchase an asset (whose price then increases) and can be used as collateral to secure additional funding (either in a refinancing or by another borrower taking out a new mortgage to purchase the house). In this example, money is created solely for the purpose of purchasing a pre-existing asset, resulting in its price increase, while no value is added to the rest of the economy.

This process works as long as financial credit creation rises and collateral asset prices increase. However, when the prices of collateral asset fall (or when credit creation decreases and leads to a fall in collateral asset prices), the entire system forcibly and violently unwinds in a reversal of the bubble creation process.

Other examples of this mechanism include margin loans, repo, loans to non-bank financial institutions, loans to structured investment vehicles (securitized products such as ABS, MBS, CLOs, etc.), loans for private equity, loans for mergers and acquisitions, etc.

Lending towards consumption will create inflation but not necessarily economic growth.

Money creation for the purpose of consumption will increase the prices of the consumer items that are purchased but will not necessarily create future economic growth, because the potential for the economy to create additional useful goods and services is not expanded, the key phrase being “useful goods and services.” For example, the increased availability of student loans (and federal government guarantees) increased the price of college tuition but has not necessarily improved the quality of a college education or the productive capacity of a college graduate. The phrase “price is what you pay, value is what you get” comes to mind. Credit creation that funds consumption will increase the prices of the goods and services being consumed, but not the intrinsic value of these objects.

Lending towards productive enterprises will create future economic growth and low and stable inflation.

Lending towards productive enterprises increases the long-run productive potential of the economy. The result is an economy in which an increase in the supply of useful goods and services expands in step with an increase in the demand for said useful goods and services, leading to low and stable consumer price inflation.

The problem here is how to measure spending on “productive enterprises.” Capital expenditures and research and development by companies seem like a natural place to start, and other proxies will also be covered in future issues of Monetary Mechanics.

The simple diagram above shows the different types of activities that lending can be directed towards. Essentially, what it shows is that there are many ways in which credit creation can be unproductive, but only very few ways in which credit creation can be productive.

An additional interesting wrinkle is that the credit creation that flows into capital markets via securitization of loans or corporate bond issuance facilitates the creation of additional leverage, consequently exacerbating asset bubbles in the financial economy through the repo collateral multiplier.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

https://cdn.evbuc.com/eventlogos/67785745/turner.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521914001070?via%3Dihub

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521914001434?via%3Dihub

https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/the-case-of-the-missing-money/

https://www.nytimes.com/1979/02/05/archives/repos-key-to-leak-in-us-money-supply-a-new-key-to-leak-in-money.html

https://www.postkeynesian.net/downloads/Werner/RW301012PPT.pdf

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/01/08/Some-Alternative-Monetary-Facts-49975

Ibid.

The problem is how do you systematically identify 'productive sectors' ex ante? This is tied to the problem of industrial policy

An excellent summary