Issue #38: Milton Friedman’s Interest Rate Fallacy

Milton Friedman’s interest rate fallacy is one of the most mystifying and counterintuitive facts in modern finance. Modern economists and financial analysts often assume (and operate under the assumption) that central bankers have near complete control over interest rates, especially in the era of trigger-happy central bank officials who are all too excited to initiate asset purchases at the first sign of financial instability. The average economist and financial market participant automatically associate high interest rates with tight monetary policies and therefore tight monetary conditions in the economy, even though it goes against the evidence and experience of the past decade, as well as of the majority of economic history prior to that.

In Milton Friedman’s own words:

After the U.S. experience during the Great Depression, and after inflation and rising interest rates in the 1970s and disinflation and falling interest rates in the 1980s, I thought the fallacy of identifying tight money with high interest rates and easy money with low interest rates was dead. Apparently, old fallacies never die.1

In various previous issues of Monetary Mechanics (Issue #10, Issue #12, and Issue #19), I talked about the part that the Federal Reserve plays in setting monetary policy, how monetary policy affects the economy, and (most importantly) the fact that frequently the actual monetary conditions in the economy do not perfectly align with the applied monetary policies.

While many people have referenced Friedman’s fallacy in the past, I have not encountered an explanation that is capable of correctly and clearly explaining what Friedman is attempting to communicate. The primary problem here is that most people acknowledge and accept that interest rates are the price of credit, but pay no or almost no attention to the volume of credit. I believe that what most people associate with “easy money” is in fact not “cheap credit,” but is instead a high volume of credit. Moreover, almost everyone assumes that because interest rates are low, and credit is cheap, that credit must also be abundant, because why would it not be?

This is because almost everyone is thinking about and taking into account only the demand side – most people would love to borrow at low interest rates, so most people presume that low interest rates must mean that credit is both cheap and plentiful. However, not thinking about and taking into account the supply side of the picture, the banks and institutional investors who must make the decisions about who to lend to and at what interest rates, paints a misleading picture.

Interest Rates vs. Credit Volume

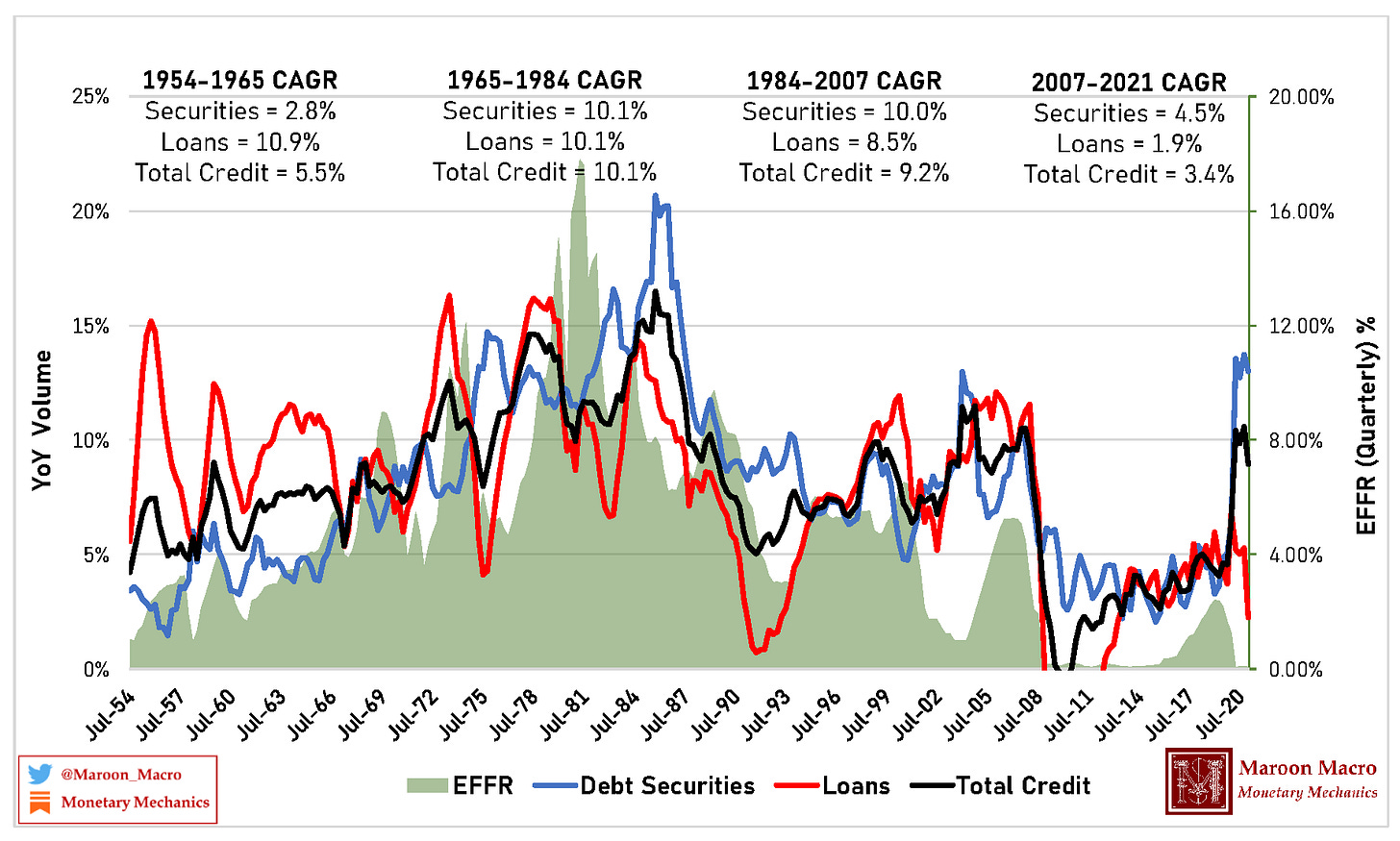

The figure above is a bit busy, so I will break down the various components.

The main feature of this figure is a demonstration of the different rates of credit issuance (through loans and bonds) in different market regimes. One can see that before 1965, loans were the dominant form of credit extension, and that after 1984, bonds became the dominant form of credit extension. The left axis denotes the year-over-year volume of credit issuance.

The right axis and shaded green area denote the Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR) throughout the same period of time. The EFFR functions as a proxy for the general level of interest rates in the economy. One can see that there is a strong correlation between the volume of credit issuance and the level of interest rates in the opposite direction that many might expect. Consequently, the periods of time with the highest volume of credit issuance are also the periods of time with the highest level of interest rates.

According to traditional economic theory, high levels of interest rates lead to reduced levels of credit issuance (through loans and bonds) because high levels of interest rates increase the cost of borrowing. According to the figure above, however, it seems that markets are totally indifferent to the level of interest rates. In fact, the volume of credit issuance and the level of interest rates seem to exhibit a positive, not negative, correlation. Basically, what this means is that low levels of interest rates tend to correspond to market regimes with low levels of credit issuance.

One can also see the same positive correlation between the volume of credit issuance and the level of interest rates during several other periods of time, including the period immediately preceding and following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, as well as the re-emergence of the private Federal Funds market after the Treasury-Federal Reserve Accord in the mid-1950s.

Both of the figures above show the same strange positive correlation between borrowing volumes and interest rate levels. What is going on here?

I believe that Friedman’s fallacy is best understood through the lens of borrowers as engaging in active liability management and as bidding for funding/financing. During more prosperous times, when the economy is rapidly and robustly growing, businesses and financial institutions are happy to keep extending credit at ever increasing interest rates, because the returns on invested capital are high. During less prosperous times, when the economy is uncertain, fewer businesses are willing to leverage their balance sheets, and perhaps much more importantly, fewer financial institutions are willing to extend credit to all but the largest and most reputable borrowers.

Now, some people may argue that during the recent period of record low interest rates, all sorts of companies have been able to obtain funding/financing, and we have seen a junk bond explosion like never before. There is some truth to that argument, as funding/financing terms are at some of the easiest as they have been in decades, and junk bond spreads are at lows like never before.

However, the focus on junk bonds misses a few important points. Credit markets, while not as liquid and tradable as equity or rates markets, are still liquid and tradable markets, unlike bank loans. Hence, an equivalent credit should trade more expensively as a security than as a bank loan because the buyer of the security can always sell the security in a fire sale when necessary.

In addition, credit market instruments can be bought by institutional investors who are not beholden to the same burdensome legislations/regulations that banks have become subject to since the GFC. These institutional investors have much more balance sheet capacity to hold instruments of questionable creditworthiness than global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), who are far more focused on maintaining their liquidity coverage ratios (LCRs), staying within their supplementary leverage ratios (SLRs), and generally maximizing profit per unit of balance sheet space (usually through nettable activity or by selling bespoke or exotic derivatives).

When judging whether or not the entire economy is “overleveraged,” it is important to look at the bigger picture. This means not just looking at the record amount of debt securities that Apple is able to issue at rock-bottom interest rates, or even the ease with which private equity firms are able to issue leveraged loans from their portfolio companies, but also looking at what the vast majority of regular small and medium sized businesses are doing. Thus, it is not what you see, but what you do not see, that is most important.

If credit was really as cheap and widely available/accessible as it is often claimed to be, then why have annual small business loan originations still not recovered and reached levels seen in the early 2000s? This is because small businesses have unquantifiable risks and are truly risky, not only in the sense of potential default risk, but much more importantly in the sense of liquidity risk. Consequently, one can very easily see tight monetary conditions among the 60-80% of small and medium sized private businesses that power the US economy but are not large or creditworthy enough to issue publicly traded debt securities.

In summary, Friedman’s fallacy is derived from two fundamental, yet counterintuitive, observations of economic history. One, when the economy is rapidly and robustly growing, and there are plenty of profitable investment opportunities, interest rates tend to increase, as both financial and non-financial institutions bid for funding/financing to take advantage of the differential between the current interest rates and the future returns on invested capital. Two, rather than differentiate between good or bad credit based only on price (via higher or lower interest rates), banks and institutional investors also differentiate between good or bad credit based on access, so that uncreditworthy businesses are altogether excluded from global debt markets, counterintuitively causing falling, rather than rising, interest rates as credit is contracting.

In conclusion, one can theorize that falling interest rates can be indicative of tight monetary conditions in the economy in the sense that demand for credit is falling (due to explanation one) and/or access to debt funding/financing is limited to just the largest and most creditworthy businesses (due to explanation two).2

Milton Friedman, “Reviving Japan,” Hoover Digest, April 30, 1998. Also see for more information: “Milton Friedman on Money,” EconTalk, August 28, 2006.

The second explanation is not unlike what happened during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic-driven recession, where employment and labor force participation fell as wages rose because the lowest paid employees were furloughed or laid off. In this case, wages were not actually rising across the economy, particularly when one takes into account the low paid hospitality workers, such as restaurant hosts and servers, who were furloughed or laid off.

Other than what's already been discussed: A glaringly obvious point - reverse causality. When the economy is good and credit is heating up, the Fed raises rates, and vice versa.

Thanks!