Issue #19: Monetary Policies vs. Monetary Conditions

The Translation of Monetary Policies into Monetary Conditions

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I discuss in detail the differences between the Federal Reserve’s intended monetary policy stance and actual monetary conditions in the real and financial economy. Although many people believe that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policies are automatically and perfectly transmitted through the real and financial economy, working as they are originally designed to do, I believe that that is not the case. In previous issues of Monetary Mechanics, Issue #10 and Issue #12, I discussed in depth the plethora of moving parts involved in the implementation of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policies, all of which must work in sync for the Federal Reserve to be able to successfully influence monetary conditions.

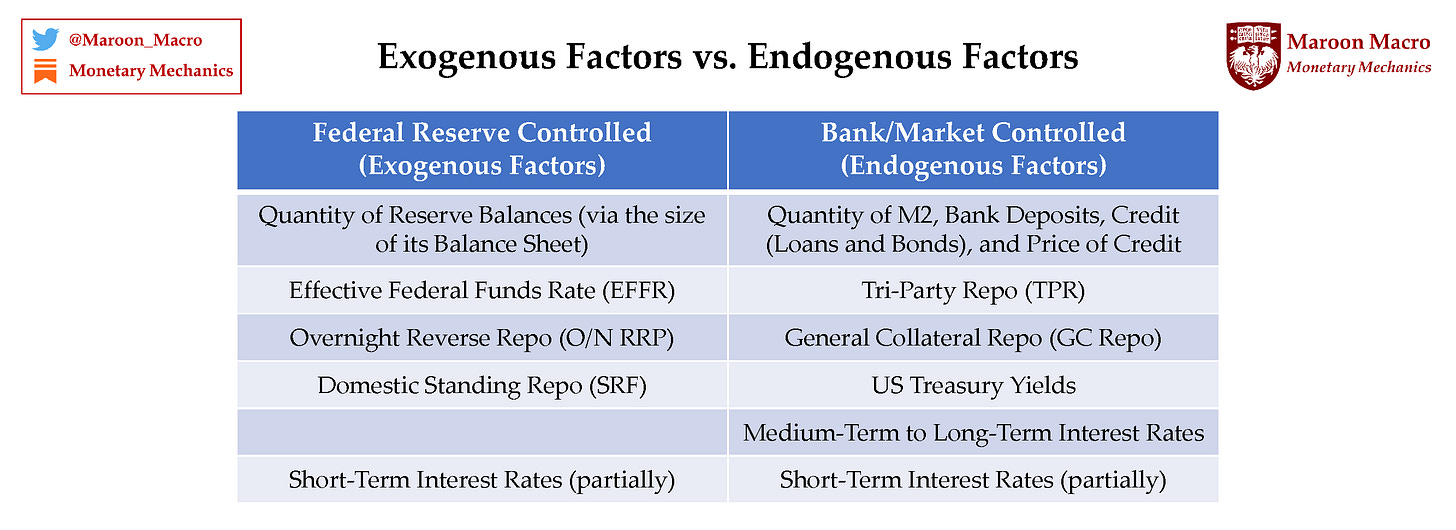

We can call the Federal Reserve’s attempts to implement monetary policies “exogenous” to the banking system itself (i.e. the Federal Reserve’s decisions are out of the control of banks). However, the resultant effect on the economy (i.e. the quantity and price of loan extension/bond issuance and credit creation) is “endogenous” to the banking system itself, as banks themselves can choose how many loans they want to make and at what interest rates they want to lend at. Since we no longer use physical currency as a primary means of settlement, the vast majority of the “money creation” in the real economy is a result of the collective actions of the commercial banking system (i.e. making loans/issuing deposits).

Therefore, the Federal Reserve attempts to implement monetary policies and influence the aggregate behavior of the commercial banking system by manipulating interest rates and changing the cost of funding/financing for banks. The traditional theory is that lower short-term interest rates should lower the cost of marginal funding/financing for banks, which should encourage them to extend more loans (at lower and lower rates), which should lower the cost and increase the availability/accessibility of credit for consumers, easing monetary conditions throughout the economy.

In theory, the translation of monetary policies into monetary conditions is supposed to be simple and seamless. Lowering the federal funds rate (FF) is supposed to lower the cost of funding/financing for banks, which is supposed to simultaneously increase the volume of credit and decrease the price of credit (in the form of loans/bonds). In practice, however, as discussed in Issue #10 and Issue #12 of Monetary Mechanics, the translation of monetary policies into monetary conditions is far more difficult than the Federal Reserve dictating what short-term interest rates are supposed to be set at and the market falling in line. Hence, for the transmission of monetary policies to function as planned/promised, financial market participants (e.g. banks, dealers, hedge funds, etc.) must conduct arbitrage to “police” interest rates into their “proper” places.

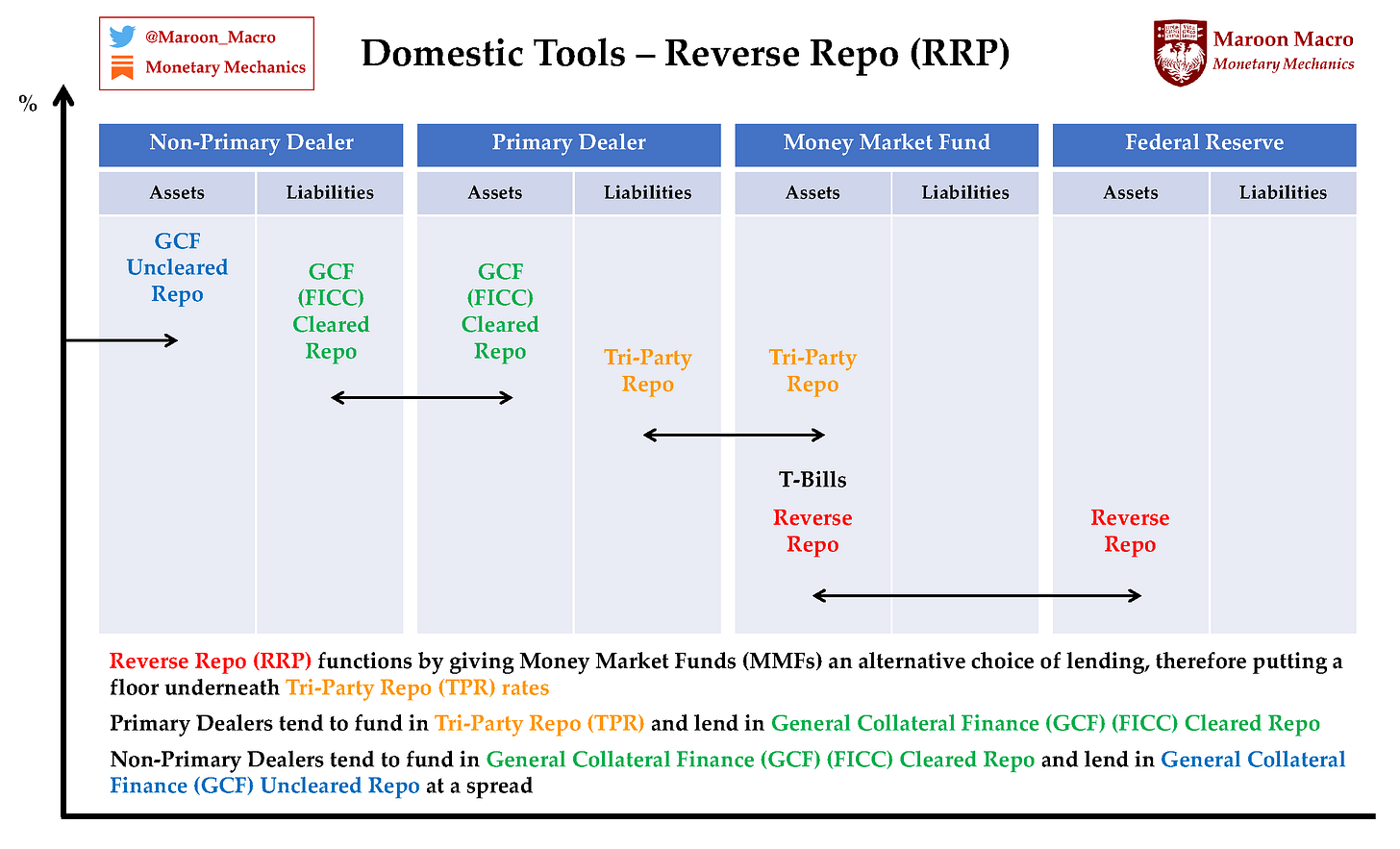

A prime example of a failure of the proper transmission of monetary policies (one that I have not fully discussed yet) is how the interest rate on excess reserves (IOER) was intended to function as a (soft) ceiling for the general collateral (GC) repo rate. The GC repo rate is the rate at which large dealers (who are large enough to borrow at lower tri-party repo rates) fund smaller dealers (who are not large enough to borrow at lower tri-party repo rates). The GC repo rate is also used as a benchmark for overnight repo funding for other financial investors (e.g. hedge funds who borrow either in sponsored repo or in uncleared bilateral repo at GC repo plus a spread).

While banks that are allowed to earn IOER are able to lend into GC repo, these banks typically chose not to, because IOER tended to be higher than either tri-party repo or GC repo (outside of quarter-end spikes due to “window dressing” where regulated entities reduced their risky activities that had high balance sheet impacts). The idea was that banks would willingly lend into the repo market if and when the GC repo rate ever rose above the IOER (i.e. if/when dealers were risk-averse or “out of capacity” for whatever reason – basically if/when balance sheet was scarce). The reasoning behind this was that holding reserve balances and reverse repurchase agreements (RRPs) are almost neutral from a risk-management and regulatory perspective (there are some subtle differences pertaining to banks’ own preferences for “T+0” liquidity vs. “T+1” liquidity and how Dodd-Frank’s “living wills” or resolution planning incentivize the holding of such liquidity buffers).

The important thing to note about all of this is that it did not work, as laid bare by the September 2019 repo spike. If the Federal Reserve cannot control short-term interest rates, like it is supposed to do, how is it supposed to control the broader economy, something that is far more complex and out of its direct control?

The Divergence of Monetary Conditions from Monetary Policies

Generally, when one talks about monetary conditions in the real and financial economy, one is referring to the Federal Reserve’s intended monetary policy stance with the implicit assumption that it is automatically and perfectly transmitted through the real and financial economy, so that actual monetary conditions (i.e. the quantity, price, and availability/accessibility of credit) are never that far off of the central bank’s design. While officials, commentators, investors, and other financial market participants may disagree and argue over whether they believe the Federal Reserve is being “too dovish” or “too hawkish” for their liking, the fundamental ability of the central bank to properly control monetary conditions is usually never questioned. But, as mentioned in previous issues of Monetary Mechanics, as well as by former central bankers themselves, what if central bankers do not have a large degree of control?1 2

I have already demonstrated that central bankers do not have absolute control over the short-term funding markets – central bankers may, in fact, have very minimal direct control over the short-term funding markets, depending predominantly on the induced buying and selling behaviors of other financial market participants to enact their agendas. This is particularly true in the post-GFC period, as the governing philosophy of central bankers has changed from a regime of “scarce” reserves to a regime of “abundant” reserves and from a corridor system to a floor system and finally back to a form of a corridor system. Moreover, central bankers also do not have absolute control over the behavior of the market – marginal funding being more expensive led to a proliferation of “risk-free” arbitrages in the form of negative interest rate swap spreads, deviations from covered interest rate parity (CIP), and the GC repo rate being higher than the IOER.

Is “Easy Money” Cheap Credit or Widely Available Credit?

Finally, a worthwhile question for us to think about for a moment is whether “easy money” is supposed to be cheap credit (i.e. credit at low interest rates) or widely available credit (i.e. high volumes of loans/bonds extended/issued, as well as of other forms of credit). I believe that widely available credit – abundant credit – is far more important than cheap credit, because cheap credit means nothing for the economy and its various participants if it is not easily accessible to them.

Credit Creation and Growth during Various Market Regimes

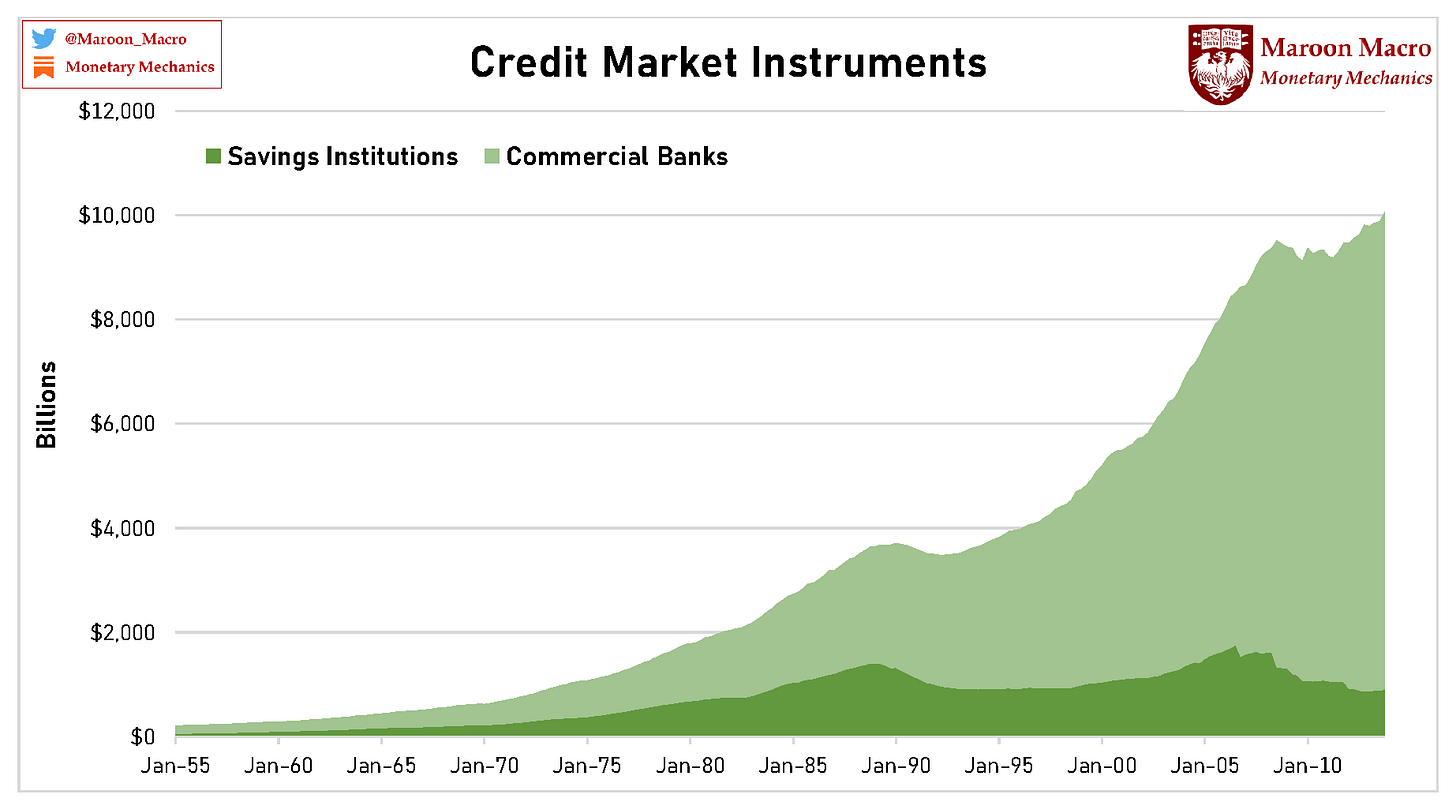

What people mean when people say “easy money” post-GFC is essentially easy bond issuance at low interest rates for S&P 500 companies, instead of cheap and widely available credit for the entire economy. However, relative to that during prior financial and economic regimes, total credit creation and growth post-GFC is completely abysmal (3.4% CAGR since 2007). The figure above shows that bond growth has been fairly anemic and loan growth has been practically nonexistent since 2007. Contrary to the theoretical understanding of the relationship between interest rates and monetary conditions, the volume and availability of credit has not picked up since the GFC, despite rock-bottom interest rates. Paradoxically, the period of greatest total credit volume and availability coincided with the period of highest interest rates (in the 1970s and the 1980s).

Milton Friedman remarked in the 1960s:

As an empirical matter, low interest rates are a sign that monetary policy has been tight – in the sense that the quantity of money has grown slowly; high interest rates are a sign that monetary policy has been easy – in the sense that the quantity of money has grown rapidly. The broadest facts of experience run in precisely the opposite direction from that which the financial community and academic economists have all generally taken for granted.3

In future issues of Monetary Mechanics, I will further discuss Milton Friedman’s interest rate fallacy, as well as incentives for bank balance sheet expansion. However, let it suffice to say for the moment that low interest rates are actually a sign of tight money in the real economy, as high interest rates are generally associated with a high volume of credit in the real economy. The process that takes place behind this is that when business opportunities are plentiful (i.e. there are lots of potential for business expansions), there is a higher loan demand, a demand that banks are happy to accommodate, which causes a higher credit volume.

Furthermore, higher risk-free interest rates signify the existence of higher economic growth potential, as risk-free interest rates are the opportunity cost of capital. Why would anybody buy a US Treasury security that yields less than inflation if there were plentiful business opportunities with much higher risk-adjusted returns? Consequently, economic growth will generally drag up interest rates over time, as banks attempt to accommodate the higher and higher credit demand by buying funding at higher and higher prices.4 5

I am not making an argument for one side or another, about whether or not credit is “fairly priced” today. I am merely making the argument that what most people think of as “easy money” is only the cheapness of credit, with the availability of credit only as an afterthought. The assumption made here is that if credit is cheap, credit must therefore be widely available too, but that is not necessarily the case, especially as bank balance sheet space has become far more expensive with post-GFC Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) and Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) regulations setting limits on both the size and the composition of bank balance sheets. This is all without taking into consideration the trillions of low yielding deposits and reserves that were created as a byproduct of quantitative easing.

“When I was at the Federal Reserve, I occasionally observed that monetary policy is 98 percent talk and only two percent action.” (https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-bernanke/2015/03/30/inaugurating-a-new-blog/).

“If the Fed’s control of long-term rates depends in substantial part on the induced buying and selling behavior of other investors, our grip on the steering wheel is not as tight as it otherwise might be.” (https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/stein20130926a.htm).

Milton Friedman, “The Role of Monetary Policy,” in Essential Readings in Economics, Palgrave Macmillan, 1995, pp. 215-231.

Richard A. Werner, “The Relationship Between Interest Rates and Economic Activity: How the Conventional Literature has Dealt with the Japanese Experience,” Japanese Fixed Income Markets: Money, Bond and Interest Rate Derivatives, Elsevier, 2006, pp. 135-170.

Richard A. Werner, “The “Enigma” of Japanese Policy Ineffectiveness: The Limits of Traditional Approaches, Not Cyclical Policy,” The Japanese Economy, Vol. 30, No. 1, M. E. Sharpe, 2003, pp. 25-95.

Interesting piece. I would venture that policy changes since the GFC have likely tightened the link between policy and conditions. But this may unravel. Also if ‘Liquidity’ is in some sense a measure of the b/s capacity of financial intermediaries, it may be worth considering what drives each side of the financial sector b/s and whether assets or liabilities are exogenous or endogenous factors…. or both?