Issue #42: The Origins and Evolution of the Modern Monetary System

Part 7: "Liability Management" – Commercial Paper (CP)

Recall that there are a few fundamental innovations that have radically transformed our monetary and banking system in the post-WWII era:

Liability Management (a.k.a. “wholesale finance”) – the expansion of banking strategy that transformed banks from passive acceptors of deposits to aggressive operators in the money market. This includes federal funds borrowing/lending, repo, commercial paper, money market funds, eurocurrency/eurodollar banking, and much more.

Securitization (a.k.a. “market-based finance”) – the disintermediation of traditional commercial bank lending in favor of bonds and the pooling of illiquid, untradable loans to form liquid, tradable securities. This includes the proliferation of mortgage-backed securities, high-yield bonds, increased IG corporate bond issuance vs. loans, and other asset-backed securitizations. This also coincided with the advent of the pension system, which indirectly funneled America’s future retirement savings into the financial market.

OTC Derivatives and Value-at-Risk (VaR) – combined with Basel risk-weightings, these innovations introduced increasingly esoteric and mathematical definitions of “money-ness,” resulting in the redefinition of money as “bank balance sheet capacity.” This also cemented the shift of bank business models towards fee-generating, off-balance sheet banking activity as opposed to maturity transformation based on net interest margin or balance sheet expanding arbitrage.

In the first issue of this installment, I covered “asset management” (the traditional model of banking, in the form of deposit-taking and lending), which we can build upon to begin to understand exactly how and why our modern financial system is so different from the textbook description of deposits, reserve requirements, and money multiplication. In the second issue of this installment, I covered the first part of “liability management” and the re-emergence of wholesale finance, focusing on the development of the domestic federal funds market. In the third issue of this installment, I covered the second part of “liability management” and the re-emergence of wholesale finance, focusing on the development of the international Eurocurrency/Eurodollar banking system. In the fourth issue of this installment, I continued covering the development of the international Eurocurrency/Eurodollar banking system, focusing on the entrance of US banks into the Eurocurrency/Eurodollar borrowing and lending market. In the fifth issue of this installment, I covered the third part of “liability management” and the re-emergence of wholesale finance, focusing on the development of large negotiable certificates of deposit (CDs). In the sixth issue of this installment, I covered the fourth part of “liability management” and the re-emergence of wholesale finance, focusing on the development of bank holding companies (BHCs).

If you have not had a chance to read Issue #8, Issue #11, Issue #16, Issue #28, Issue #33, and Issue #41 of Monetary Mechanics yet, I suggest you do before continuing below, as it contains important information, but here is a brief review for you if you need it:

Commercial banks create new money (deposits) when they extend new loans. Banks are simultaneously limited by statutory reserve requirements (prior to March 2020) and, more importantly, by self-imposed liquidity constraints. Banks need reserves to settle transactions and payments with other banks, such as when deposits are transferred, or when an individual or business pays another in bank deposits. In a world without a private market for Federal Funds, daylight overdrafts on Fedwire, or the ability to regularly borrow from the Federal Reserve’s discount window, banks depended on attaining and retaining deposits to replenish their reserves.

These limitations defined the relatively more repressed financial regime of the early post-WWII era (as contrasted against that of the 1960s-2010s). Prior experiments with the liberalization of money and banking in the early 20th century, coupled with the subsequent Great Depression and the period of financial repression during WWII, left people skeptical about the benefits of a liberalized money and banking system.

The development of the private market for Federal Funds permitted large money-center banks to borrow reserves from small countryside banks, enabling large money-center banks to deliberately operate with a structural short position, where they lent more than they had reserves on hand, knowing that they could borrow the difference in the federal funds market, for the purpose of expanding their marginal lending activities. More importantly, the development of the private market for Federal Funds spearheaded the redevelopment of an informal interbank network that, together with other methods of liability management that I will soon cover in this and other issues of Monetary Mechanics, began to transform the model of banking from a deposit-facing one to an interbank-focused one.

As US dollar deposits found their way offshore and onto the balance sheets of banks in London, Paris, Frankfurt, and Zurich, the Eurocurrency/Eurodollar banking system emerged as a supranational, informal interbank network that linked the world’s various financial systems into one tightly woven web. Consequently, this evolution led to the emergence of a structure of international interest rates that were (and still are) distinct from, as well as largely independent of, national interest rates – a development that is without parallel in modern economic history.

As US dollar deposits found their way offshore, the onshore market also developed new and much more flexible forms of bank deposits that allowed banks to lock up funding/financing at flexible rates for longer periods, resulting in banks being able to “bid” for funding/financing. The development of large negotiable certificates of deposit (CDs) in 1961 transformed the traditionally illiquid retail and corporate time deposit into a truly liquid money market instrument. Consequently, this broadened and diversified the menu of liability management options offered to banks, permitting banks to better optimize their balance sheet structures, as well as permitting banks to circumvent the Federal Reserve and continue providing credit to their most important clients/customers, even in times of tight monetary policies.

During the same time as this evolution of new monetary techniques, new legal and regulatory measures also evolved, allowing banks to conduct a broader array of activities than before. The assortment of asset and liability management options available, first to one-bank holding companies and then later to multi-bank holding companies, facilitated the proliferation of all the aforementioned activities (e.g. federal funds borrowing/lending, eurocurrency/eurodollar banking, and large negotiable certificates of deposit), as well as permitted banks to provide novel types of liabilities (e.g. commercial paper). Consequently, the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, and its amendments, constituted a landmark piece of financial legislation that formed one of the first steps in a long road of financial deregulation that broadened the range of permissible non-banking activities for banks.

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I will cover certain changes to the money and banking paradigm that can collectively be called “liability management” and the re-emergence of “wholesale finance.” While there is a myriad of other financial and regulatory developments that I could fill an entire book (if not several books) about, I will attempt to cover some of the most important developments that are still relevant to and required for the functioning of our monetary and banking system today.

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I will cover the fifth major innovation in liability management, which is the expansion of commercial paper (CP) during the 1960s and the 1970s. While CP had been a staple of American finance for more than 100 years, it was the passage of the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, which clarified the legal and regulatory status of BHCs, that enabled them to issue CP from their nonbank subsidiaries, where it was exempt from reserve requirements, interest rate ceilings, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insurance premiums.1 Since there are too many important topics to cover here all at once, in future issues of Monetary Mechanics, I will also attempt to cover:

The development of the repurchase agreement (repo) market by government securities dealers shortly after WWII

Before I begin, I want to emphasize that I believe this is the single most important yet misunderstood transformation in the global monetary and banking system in the post-WWII era. This is perhaps due to the fact that many academics, analysts, and financial market participants choose to focus heavily on the development of the “shadow banking” sector during the 1980s and the 1990s (including securitization, ABCP conduits, OTC derivatives, the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, etc.).

There is no doubt that these developments profoundly transformed the nature and function of commercial banking, as well as the rest of the financial system. However, I believe that the groundwork for this monumental transition was laid long before, and, as a result, we can only tackle the problems that the financial system faces today by understanding the changing of bank behavior that facilitated banks’ shift from passive acceptors of deposits to active operators in the money markets.

Due to quantitative data limitations, I will utilize mostly qualitative data in the form of narrative exposition and evidence from reputable sources. However, I will also utilize objective numerical measures where available, accessible, and relevant.

What is Commercial Paper (CP)?

Commercial paper (CP) is a special type of short-term unsecured liability that is sold at a discount (like US Treasury bills) by financial institutions (e.g. bank holding companies, financial holding companies, etc.), non-financial institutions (e.g. regular companies/corporations), and special purpose vehicles (SPVs), indirectly to dealers or directly to money market investors.

One of the primary advantages of issuing CP, as opposed to other forms of liabilities (e.g. bonds), is that any CP with an original maturity of less than 270 days that is used to fund/finance current transactions is exempt from securities registration requirements from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).2 Generally, most CP has a maturity somewhere between 5 days and 45 days with 30-35 days being the average maturity.

There are 3 main classes of commercial paper (CP): financial commercial paper, non-financial commercial paper, and asset-backed commercial paper.

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I will primarily talk about financial CP, as it plays a major part in the development of liability management during the 1960s and the 1970s. However, for the sake of completeness, I will also briefly talk about non-financial CP, which provides a good segue into the next segment of this series on the origins and evolution of the modern monetary system, where I will tackle the disintermediation of the bank-based financial system. In a future issue of Monetary Mechanics, I will finally talk about SPVs and asset-backed CP together with the development of securitization, OTC derivatives, value-at-risk (VaR), and other more modern financial innovations during the late 1980s and the early 1990s.

The History of the Commercial Paper (CP) Market

CP was the name for a variety of notes, drafts, bills of exchange, and bankers’ acceptances that represented trade receivables and trade acceptances that were given by buyers to manufacturers and merchants in exchange for goods. These documents typically had short-term tenors, typically not more than 30 or 60 days. In turn, the manufacturers and merchants would sell these documents at a discount to dealers and investors in the money market.

CP has a long and deep history in the United States. CP was used perhaps as early as the late 1700s in New York while the economy of the nascent United States was struggling to develop in an economic environment in which bank credit was scarce.

The use of CP increased significantly during the mid-1800s in New York and other American financial centers while the industrial sector was booming and burgeoning and while a high immigration rate was driving a growing and prospering economy.3

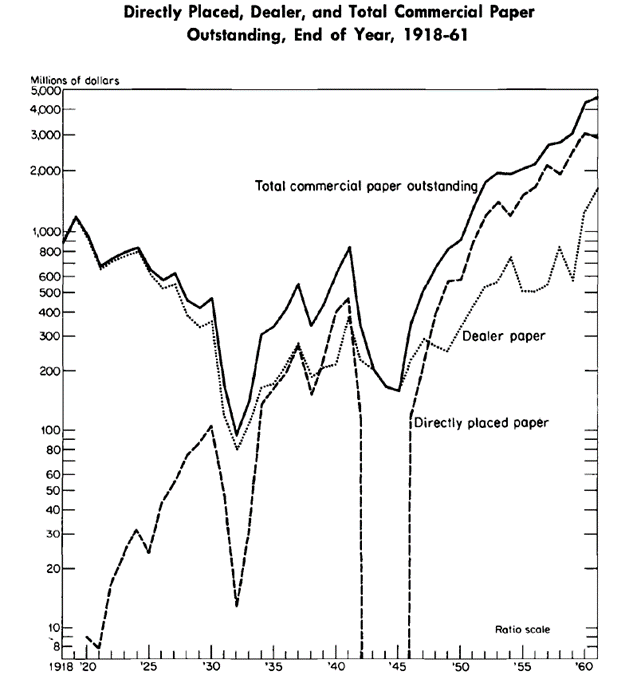

The earliest available estimate of CP outstanding is for July 1918, which is when the Federal Reserve Bank of New York started to publicly report end-of-month figures. At that time, the volume and value of CP outstanding of 30 dealers, who apparently handled virtually all CP, was $874 million, which was probably a record level.4

Banks were attracted to CP for several reasons. CP was considered a highly liquid asset, along with call loans and acceptances, despite the absence of a secondary market. CP was considered a highly liquid asset partially because of its eligibility for rediscount at Federal Reserve banks, when within 3 months of maturity. However, on a much more fundamental level, CP was considered a highly liquid asset because there was a lack of a client/customer relationship between borrowers and lenders, which largely eliminated requests for extensions and renewals.

Banks were also attracted to CP because it allowed them to diversify their risks and lend to borrowers in a broad range of industries in distant regions. In addition, CP also provided an attractive outlet for bank funds during slack periods, as CP furnished favorable yields relative to those of most other assets in 1920. During the 1920s, the CP market was a major source of bank funds, even though the CP market was only a minor source of short-term business funds. At that time, few, if any, financial companies/corporations funded their operations and investments with the CP market.

The immediate post-WWII period produced a perceptible resurgence of the CP market, and, as the figure above shows, the CP market almost recovered to its 1920 peak by 1951. However, the CP market had changed substantially compared to its early days. On the issuer side of the CP market, directly placed CP, which was predominantly CP that was issued by the 3 largest financial companies/corporations, increased to about ⅔ of all CP outstanding by the early 1950s. On the investor side of the CP market, non-financial companies/corporations started to invest liquid assets in CP instead of continuing to strictly stow liquid assets in demand deposit accounts. At the same time, banks were relying to a much greater extent on US Treasury securities, rather than on CP, as secondary reserve assets.

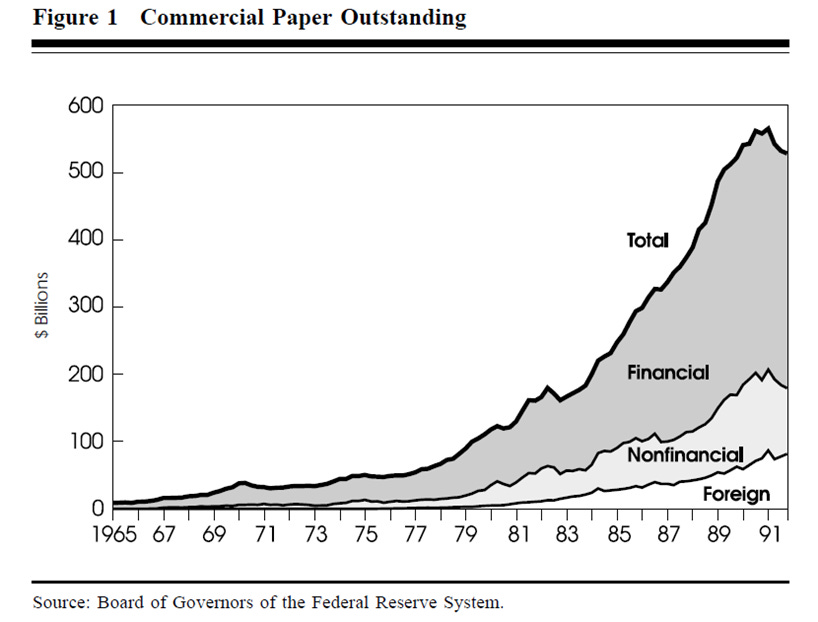

There were two events that stimulated the extraordinary expansion of CP during the 1960s. First, during the last three quarters of 1966, market interest rates rose above Regulation Q ceilings for negotiable certificates of deposit (CDs), which made it more difficult for banks to raise funds to meet the strong demand for corporate loans. Without sufficient funds for corporate lending, banks called on their financially strongest clients/customers to issue CP, as well as offered backup lines of credit themselves (an arrangement akin to the backup lines of credit offered to asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) conduits that facilitated funding for collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) during the early 2000s). Consequently, the annual growth rate of total outstanding CP increased all the way from 7.8% in 1965 to 46.6% in 1966.

Second, in 1969, credit market tightness reoccurred, as market interest rates rose above Regulation Q ceilings again. A flurry of financial innovations by banks, including the sale of CP by bank holding companies, gave rise to the growth of CP. Consequently, the annual growth rate of total outstanding CP increased further to 54.7% in 1969. However, in August 1970, the Federal Reserve implemented a reserve requirement on funds fetched in the CP market and channeled by a bank holding company to any of its member bank subsidiaries and affiliates. Hence, as a result, bank-issued CP dropped dramatically in 1970 and 1971. However, this episode was only a temporary interruption to the long-term growth of bank-issued CP, which returned to its former prominence and further proliferated during the mid-1970s.

How is Commercial Paper (CP) Used?

Naturally, different types of firms issue CP for different reasons. Financial companies/corporations, including bank holding companies, issue CP to raise funds on a more or less continuous and consistent basis to support both individual and corporate lending (i.e. for short-term liquidity adjustment). Non-financial companies/corporations issue CP to raise funds at less frequent intervals for short-term expenditures such as inventories, payrolls, and tax liabilities.

As stated in Issue #41 of Monetary Mechanics, one-bank holding companies were not classified as bank holding companies for legal/regulatory purposes, which permitted them to raise funding through their nonbank subsidiaries in the CP market.

The way that this typically worked was that commercial banks that needed additional funds would frequently sell portions of their loan portfolios to their own holding companies. This was easily done because bank client/customer notes were negotiable instruments. Then, the holding companies would use the underlying credit of the banks that they own to sell large amounts of CP in the money market to raise the required funds to purchase the loan portfolios. Then, the required funds raised by the issuing of CP by the holding companies would be transferred to the commercial banks, which would use the funds to expand their investment portfolios. In addition, the commercial banks would also use the funds to finance any immediately pressing liquidity issues, such as deposit withdrawals.5

This indirect method is much more advantageous than the direct issuance of CP by the subsidiaries and affiliates of commercial banks, because funds secured by bank holding companies were not treated as deposits, and therefore were not subject to the Federal Reserve System’s reserve requirements and interest rate ceilings under Regulation D and Regulation Q (at least up until 1970).6

The Problems with How Commercial Paper (CP) is Used

The CP market has generally been dominated by large companies/corporations with the highest credit ratings, because CP is unsecured, and thus the only thing backing up the promise to repay the investor is the word and reputation of the issuer. However, in spite of its self-selecting nature, the CP market has frequently been vulnerable to runs throughout the past few decades. Furthermore, most CP is issued with the assumption that it can be regularly “rolled over,” so a sudden drying up of financial conditions can be catastrophic for both financial and non-financial companies/corporations and their ability to fulfill their short-term liquidity needs. This was exactly what happened with Penn Central Transportation Company during the Commercial Paper Liquidity Crisis of 1970.7

Conclusion

Another consequence of the increased usage of CP during the 1960s and the 1970s, aside from the aforementioned benefit of more options and more flexibility in liability management for bank holding companies, is that non-financial firms attained more familiarity with market-based finance, as opposed to bank-based finance, and gradually reduced their reliance on short-term bank loans. For corporate borrowers, the use of capital and money market funding was much less costly than the use of short-term bank loans, consequently conferring substantial savings. As a result, financially sound non-financial firms started to depend to an increasingly degree on the CP market for short-term credit.

This transition provides a prelude to the larger disintermediation of bank-based finance that occurred during the 1980s and the 1990s, as firms began to take advantage of the more diversified, more flexible, and cheaper funding options offered by capital and money markets. Consequently, it was this transition that sowed the seeds for the wave of securitization and market-based finance that still dominates the monetary system today.

Leon B. Gould, “Banks and the Commercial Paper Market,” Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 25, No. 6, November-December 1969, pp. 25-28. Also available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4470597.

Peter A. Abken, “Commercial Paper,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Review, Vol. 67, No. 2, March/April 1981, pp. 11-21. Also available at: https://www.richmondfed.org/~/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/economic_review/1981/pdf/er670202.pdf.

Jerry R. Marlatt, “Market Trends 2020/21: Commercial Paper,” Mayer Brown LLP. Also available at: https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/perspectives-events/publications/2021/04/market-trends-202021_commercial-paper.pdf.

Richard T. Selden, “Four Decades of Change in the Commercial Paper Market,” Trends and Cycles in the Commercial Paper Market, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1963, pp. 6-30. Also available at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c1919/c1919.pdf.

Donald E. Fleming, “An Analysis of the Effects of the Practice of Liability Management by Large Commercial Banks: 1960-1972,” A Dissertation in Business Administration, Texas Tech University, December 1974. Also available at: https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/bitstream/handle/2346/17077/31295001371631.pdf.

Kenneth V. Handal, “The Commercial Paper Market and the Securities Acts,” University of Chicago Law Review, Vol. 39, Iss. 2, Article 6, 1972. Also available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3723&context=uclrev.

Kaleb B. Nygaard, “1970 Commercial Paper Market Liquidity Crisis (U.S. Historical),” The Journal of Financial Crises, Vol. 2, Iss. 3, 2020. Also available at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1108&context=journal-of-financial-crises.

Thank you for the detailed explanation. Just for the clarification purposes, in the accounting table above, you are showing that Bank Holding Company has reserves. Are they actually eligible to hold reserves at the FED? Did you actually mean deposits that they hold in their bank subsidiaries? If that is the case the purchase of the loans from the proceeds of CP issuance would just contract the balance sheet of the bank (Debit Deposits to BHC, Credit Loans) without providing any new liquidity. It might just reduce deposits liabilities and “free up” excess reserves, unless, of course, initial funds for the CPs came from other banks to begin with which would obviously add to the reserves of the commercial bank. If you can confirm I would appreciate.