Issue #39: Repo Review: Sponsored Repo

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I am going to talk about the effect of the explosion in sponsored repo on the broader short-term interest rate complex, as well as how it fits into the broader development of money markets in the post-GFC financial system. A disclaimer: I myself am not an active participant and trader in this particular market, and as such I may be incorrect about some of the specifics and the legislative and regulatory nuances of this relatively new and niche type of repo.

My objective here is to attempt to provide a high-level overview of the most fundamental features of sponsored repo to attempt to uncover and understand what (if any) effect this practice has on the rest of the global financial system. I will do my best to place sponsored repo within the proper context relative to the rest of the US repo market complex, and also to impart some informative, interesting, and useful insights about sponsored repo that may not have been fully fleshed out by other people.

Technically, sponsored repo initially appeared in 2005 with State Street as its inaugural member. However, it was not until 2017 that money market funds began participating in sponsored repo, and it took until 2019 for sponsored repo to really break out into the mainstream.1

FICC Repo Exposures in Money Market Funds

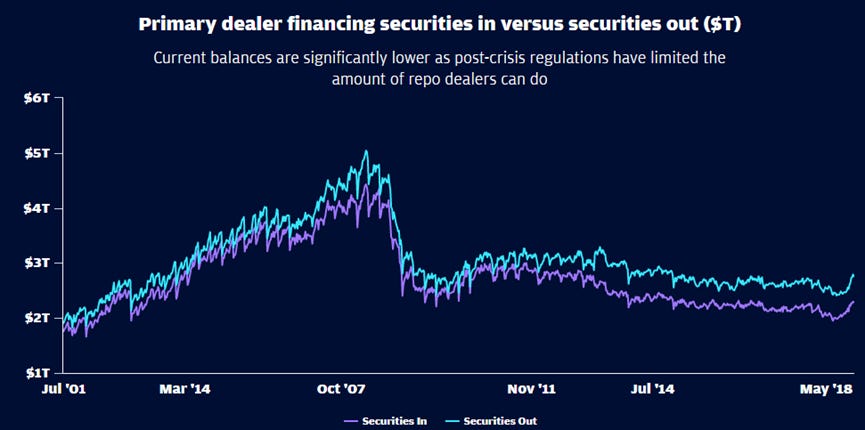

In the post-GFC period, the financial system remains chronically short of “balance sheet capacity” as a result of a combination of voluntary behavioral changes and legislative and regulatory mandates. This is something that I have already written about in various previous issues of Monetary Mechanics (Issue #20, Issue #25, Issue #26, and Issue #32). Repo has been hit particularly hard by a surge of legislative and regulatory reforms, specifically the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR).

The primary reason why repo has been hit particularly hard is because it is a high-volume but low-margin business. In the past, tight spreads were compensated with and offset by billions of dollars of volume. This, combined with the fact that repo, if done properly, is a fairly low-risk activity that is also crucial/critical to the functioning of the financial system, made repo intermediation a reliable cash cow for dealers.

This works fine in a world with elastic dealer-bank balance sheets. However, the introduction of the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR), as well as other much more intangible behavioral changes among financial market participants, changed the internal profit maximization calculation for dealers.

According to Josh Younger, a fixed income strategist at J. P. Morgan,

It’s important to note that at no point during March 2020 was [the SLR] likely to become binding, there was plenty of buffer … So why did we have the market functioning failure that we did? I think we can point in large part to not the SLR constraint itself, but the way that the SLR constraint shapes the incentives and business planning of a complicated institution like a large investment bank.2

Note that his statement has two particularly important points:

The Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) is a significant factor in constraining bank balance sheet size, thus increasing the premium on bank balance sheet space.

However, the most important constraint is not that – it is the individual risk tolerance of each and every dealer, which is affected, but not entirely dictated, by Basel III regulations and requirements.

Now, instead of being incentivized to maximize total profit regardless of balance sheet size, dealers are incentivized to maximize profit per unit of balance sheet space, or in other terms, efficiency.

What this means in practical terms is decreasing the volume of repo intermediation and increasing the volume of activities that have higher margin but lower balance sheet impact, including various types of derivatives and other nettable activities.

As an analogy, imagine a grocery store that sells a wide variety of food products, from staple products like water, milk, bread, and eggs, to luxury products like expensive confections, cakes, and wine.

If the grocery store is able to do business freely, it would most likely choose to sell a healthy mix of both staple products and luxury products according to customer desire/demand and maximize its total revenue, as that would maximize its net profit in this situation. However, if the grocery store is limited to selling only $100 worth of products, it would most likely choose to maximize the amount of low-volume but high-margin luxury products that it can sell, as that would maximize its net profit in this situation. The grocery store would still sell the bare minimum amount of staple products to ensure that its surrounding/supporting community does not simply starve to death, but that would be far less than the optimal amount of staple products that would be ideally sold, because the grocery store is not incentivized to do so.

This analogy is actually very pertinent to the operation of a dealer bank that is limited by Basel III regulations and requirements, particularly pertaining to the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR). While banks always have the option of growing the total size of their balance sheet by increasing their Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital, banks tend to measure their profit relative to a return on equity (ROE) target, thus tending to maximize profitability as opposed to total net income. Consequently, the total size of a given balance sheet is fixed, given a level of equity.

This is where sponsored repo makes a big difference. What if the grocery store is able to ignore the sales of staple products under certain conditions? The grocery store would most likely choose to increase the amount of staple products that it can sell, since these sales would add to its net profit but not contribute to its revenue limit.

This is exactly what sponsored repo enables dealer banks to do.