Recently, I authored my first issue about decentralized finance, Issue #23, in which I dipped my toes into what decentralized finance (DeFi) is and what it might mean for traditional financial markets (TradFi) in the future. In that issue, I admitted that I had become cautiously optimistic about DeFi’s potential to disrupt (and improve) the plumbing and architecture of the legacy financial system. While I still do not consider myself an expert on cryptocurrencies, digital assets, and DeFi, I have spent some time and energy researching and playing around with various protocols on different blockchains in the past few weeks and feel that I know enough to offer an update on my previous views with some more specific commentary.

First, I want to explain the evolution of my thinking about cryptocurrencies to help others understand why I have changed my mind about this extremely speculative asset type. While I have been aware of the existence of cryptocurrencies for years, it was not until very recently that I could see the use case for most of these digital assets. As regular readers would probably know, I do not subscribe to the “Fed money printer go brrr!” mindset that has led so many to become insanely bullish on Bitcoin (BTC). Therefore, the attraction of something that, upon first glance, seemed to be nothing more than another scarce asset (similar to precious metals, limited edition collectibles, real estate, or other real assets) held little allure for me. In addition, I was unfamiliar with the concept of smart contracts, as well as how Ethereum (ETH) was fundamentally different from Bitcoin (BTC).

For sure, Bitcoin (BTC) is an amazing innovation – it solves the “Byzantine Generals Problem,” a key reason why we have central banks and a few dozen large globally active dealer banks acting as the master ledger keepers for the global economy’s transactions. Basically, a system of protocols must be agreed upon by all participants for it to be valid (without such a universal and unanimous agreement, its validity will be called into question, and it will cease to be a useful measurement tool). In the earliest days of banking, it was easier to have a single master ledger keeper who kept track of everyone else’s ledgers. This eventually evolved into the modern system of central banking that we have come to comprehend today.

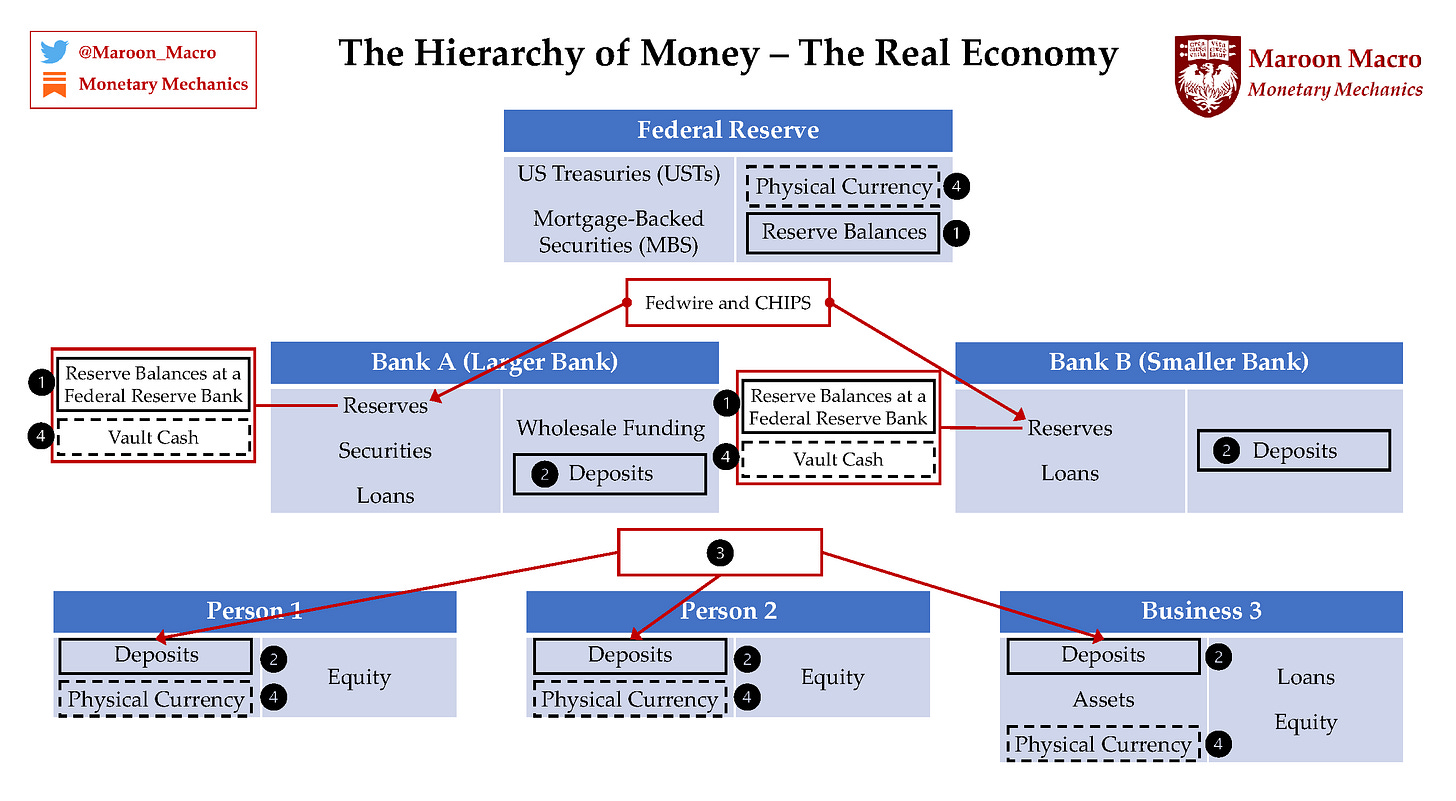

However, as the world economy began to globalize over time, especially in the post-WWII environment, the system of central banking became too rigid for the capital needs of a rapidly developing world. Then, the modern system of wholesale banking, outgrowing the stodgy dependence on central banks, took its predecessor’s place, utilizing a universal medium of exchange that fueled and facilitated international trade – the Eurodollar. While the method of final settlement still nominally remained on the books of central banks, the development of the Eurodollar banking system introduced a faster and more efficient method of intermediate settlement that affected everything that came before final settlement on central banks’ balance sheets. The Eurodollar banking system was so much faster and more efficient that the total number of bank reserves necessary for final settlement barely increased for 70 years while the total value of financial assets increased more than 100x.

In 1947, $316 billion in payments were made through Fedwire during which the stock of reserves held at Federal Reserve Banks amounted to $17.9 billion. In 2007, a whopping $670.7 trillion in payments were made through Fedwire while the stock of reserves held at Federal Reserve Banks amounted to only $9 billion.

In other words, the improvements in speed and efficiency made possible by the evolution and expansion of international wholesale banking, as well as of various securities and derivatives markets, enabled payments to increase by 212,115% while reserves simultaneously decreased by 50%.1 Payments via Fedwire do not even tell the whole story though, as we also need to consider the Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS), the other main Large Value Payment System (LVPS) in the United States. Combined, Fedwire and CHIPS processed a whopping $1 quadrillion 156 trillion in payments in 2007 (note: CHIPS nets interbank payments during the day but outstanding balances must be settled via a transfer of reserves before the opening of the next business day).2

Every transaction in the economy, except person-to-person exchanges of physical currency (i.e. bank notes and coins), must eventually flow through one of these LVPS (Fedwire and CHIPS are the largest among them, but are not the only ones).

The figures shown below include total reserves of depository institutions, which include physical vault cash held as reserves at banks. What this means is that the figures shown below would be higher than the reserve balance figures cited above ($40 billion vs. $9 billion in 2007). The figures cited above refer to reserve balances held at Federal Reserve Banks, since only reserve balances can be used to settle transactions through LVPS, not physical vault cash held as reserves at banks.

The explosion in the complexity of the economy, real and financial, was made possible through an evolution in “financial technology.” While there are many different definitions of “financial technology,” I use that term to refer to the mechanism through which payments are made (i.e. “payment rails”). Today, cryptocurrencies are generally regarded as another form of money that provides a safe store of value amidst fears of debasement of the US Dollar. While there may be some merit to that argument, and the strictly limited supply of Bitcoin (BTC) may be a critical factor in the creation of a new store of value, that is not the main reason why I am interested in this exciting and ever-evolving new field.

I am interested specifically in DeFi because I believe it harbors the potential to become a new medium of exchange, replacing the impenetrable, obscure, and inflexible layers of the wholesale Eurodollar banking system with an alternative that is rules-based, transparent, and much more flexible. On the one hand, we have this bilateral and bespoke monetary system, in which even the ruling international regulatory body (the Bank for International Settlements) is incapable of fully and properly measuring the complex web of counterparty relations. On the other hand, we have blockchains that can function as a shared ledger that is fundamentally publicly available and accessible to everyone, which ensures that all transactions are perfectly transparent to all participants, not just those involved.

I believe that we are just getting started in a decade-long development that will ultimately displace traditional mediums of exchange, not just for individual retail users, but also more importantly for the entire “plumbing” of the global financial system, at a fundamental level, which will undoubtedly lead to dramatically greater speed, efficiency, and transparency for all participants within the global financial system.

I will leave you with a passage from one of my favorite books on finance describing the development of money markets in the 1960s and 1970s, a passage that I think is also particularly relevant and applicable to the development of decentralized finance today:

The most appealing characteristic of the money market is innovation. Compared with our other financial markets, the money market is very unregulated. If someone wants to launch a new instrument or to try brokering or dealing in a new way in existing instruments, he does it. And when the idea is good, which it often is, a new facet of the market is born.3

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/01/08/Some-Alternative-Monetary-Facts-49975

Ibid.

Marcia Stigum, The Money Market: Myth, Reality, and Practice, Dow Jones-Irwin, 1978.

Extremely I'm agree:

I am interested specifically in DeFi because I believe it harbors the potential to become a new medium of exchange, replacing the impenetrable, obscure, and inflexible layers of the wholesale Eurodollar banking system with an alternative that is rules-based, transparent, and much more flexible. On the one hand, we have this bilateral and bespoke monetary system, in which even the ruling international regulatory body (the Bank for International Settlements) is incapable of fully and properly measuring the complex web of counterparty relations. On the other hand, we have blockchains that can function as a shared ledger that is fundamentally publicly available and accessible to everyone, which ensures that all transactions are perfectly transparent to all participants, not just those involved.