Issue #3: What Makes a World Reserve Currency?

Part 1: The FX Market and Cross-Border Dollar Funding

What makes a global reserve currency?

Large share of global GDP/trade

Network effect and habit/convenience/inertia – easier to stick with the USD after the suspension of gold convertibility even if that meant the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system

Military dominance/projection – ability to project military force around the globe (e.g. impose sanctions, protect shipping lanes, etc.)

1 and 3 played their respective roles (and still do to some extent) in establishing the USD as the global reserve currency after WWII, but they do not explain why it has maintained its status as the global reserve currency to this day. The US’s share of global GDP and trade is irrefutably falling. While the US military arguably has the strongest physical power projection capability (overseas bases and blue water navy), unconventional warfare is becoming increasingly important in the modern era, and other countries (especially China) are quickly catching up in this area.1 2 Moreover, military dominance and projection is only most important during a potential regime change, so it still does not explain why the USD has retained a privileged position while running massive deficits.

Consequently, we need to examine 2 more closely. Why is it convenient? For whom is it more convenient?

Individuals? Probably not, because reserve currency decisions cannot be influenced that much by the acts of individuals.

Companies? Perhaps, but companies by themselves are also likely too small to make an impact on reserve currency decisions and individual companies should be fairly agnostic as to whatever currency they use to export/import as long as funding is available.

Governments? For the United States, it is very convenient to be able to spend money and not have to worry about where it is going to come from. For the rest of the world, not so much. If the United States has been recklessly profligate for the last 20 years, why have there not been more serious challenges launched by a consortium of governments to undermine the USD’s supremacy? If foreign governments are sick of the United States for being able to skim free benefits from the rest of the world, why not stop stockpiling USD FX reserves?

We are not in the post-WWII era anymore, where the US found itself as the only national power with a functioning economy and standing military. Today, the US only consists of about 20-25% of world GDP and 10% of world trade, yet more than 60% of global FX reserves are dollar-denominated while US dollar invoicing is around 50%.3 How do we explain this discrepancy?

The answer must be something else entirely. The global banking system is the group that is actually tasked with choosing which currency to use when intermediating capital flows in the global economy, so let’s start there.

The amount of outstanding international debt securities (Eurobonds) and cross-border loans that are denominated in USD is $22.6 trillion as of Q4 2019, corresponding to about 50% of all outstanding international debt securities and cross-border loans.4 The US also has some of the largest capital markets, with about half of all IG corporate bonds outstanding being based in the US. While these statistics may shed some more light on the matter, they do not explain the dominance of the USD (especially in wholesale markets) and the “exorbitant privilege” of US Treasury securities.

Why might a Brazilian manufacturer prefer to borrow in dollars as opposed to reals? Why might an American manufacturer end up borrowing from Credit Agricole as opposed to JP Morgan?5 More importantly, why might a European institution, seeking to invest in a Thai baht asset, swap euros for dollars and then dollars for baht?6 More than half of global banks’ cross-border dollar claims do not involve a US entity on either side – how and why does this happen?7

To figure out the answer, we have to dive deeper into the wholesale financial marketplace (in contrast to the “traditional” marketplace of loans and deposits). In this research note, I will cover primarily the FX market, with a particular emphasis on FX forwards and swaps.

First Principles of a (Synthetic) Dollar Short

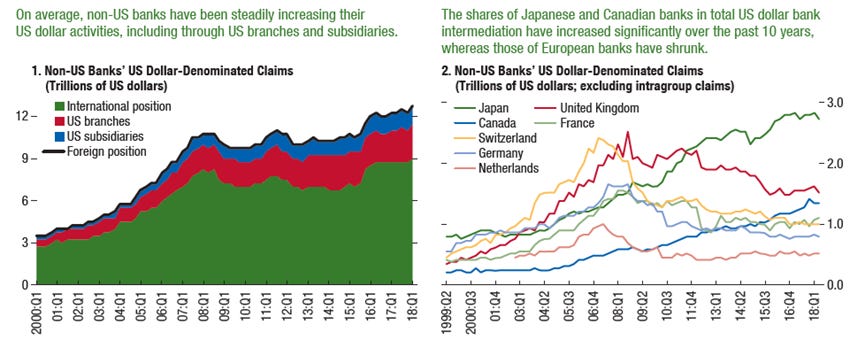

The on-balance sheet dollar-denominated assets of non-US banks have steadily increased over the past few decades. Although the market shares of various geographic regions may have shifted (i.e. European banks have stepped back after the Euro banking crisis while Canadian and Japanese banks have increased their presences), non-US banks rival the US banking system itself, based on the sheer size of their US dollar activities.8

Of particular consequence is the fact that the dollar intermediation practice of non-US banks depends largely on “wholesale” funding (i.e. interbank deposits, commercial paper, FX swaps, and repo) as opposed to traditional insured deposit type funding. 50% or more of the international dollar balance sheet (“Eurodollar” activity) of non-US banks is funded in wholesale short-term funding markets.9 10

When an agent wishes to acquire a US dollar asset on a hedged basis, they can do so in four ways:

Borrow dollars on an uncollateralized basis

Enter a repo

Enter an FX forward/swap

Combine a spot purchase of dollars with a forward sale

Thanks to the financial crisis, unsecured interbank borrowing markets have shrunk to a fraction of their former size, so this is not a feasible method anymore. Moreover, it is only when an agent already has revenue streams and wishes to hedge them that they can use a forward with ease, so that leaves either repos or FX swaps as the only viable options for most financial intermediaries.

Here are some estimates of the size and composition of the FX forwards/swaps market according to the BIS:

FX forwards and swaps – $4.3 trillion daily, $86 trillion outstanding (US dollar is 90% of the total and 96% of the interdealer total). FX forwards and swaps are the main instruments behind the growth in overall FX trading, since their combined share of overall FX turnover is more than 70%.11 The US dollar is the main currency against every currency, even among Euro currencies (i.e. Norwegian krone, Swedish krona, Polish zloty vs. the euro).12

FX forwards and swaps are primarily short-term, with about 75% maturing in less than 1 month.

Non-US banks’ gross exposure to FX forwards and swaps exceeds $30 trillion, which is more than double the $13 trillion that is their on-balance sheet dollar debt.13

Non-US non-banks (i.e. other financial intermediaries outside the US) have about $18 trillion outstanding in FX forwards and swaps vs. $11.9 trillion in on-balance sheet debt.

FX forwards and swaps differ from most other types of OTC derivatives in one crucial aspect: the full notional value is actually exchanged (as opposed to acting as a reference for the much smaller gross market value).

Furthermore, the accounting of FX swaps differs tremendously from that of other forms of secured borrowing in that it does not affect the balance sheet. A bank may have dollar obligations worth several times its total on-balance sheet assets, but they only show up in the footnotes.

Unfortunately, due to a lack of data collection, as well as difficulties reconciling data collected across national boundaries and regulatory regimes, these estimates are preliminary. However, they are enough for us to grasp the bigger picture. Non-US financial institutions (banks and non-banks) hold large amounts of US dollar-denominated assets that they fund with on- and off-balance sheet US dollar liabilities. While their US dollar-denominated assets may be long-term (1 year or longer), their US dollar liabilities tend to be short-term (overnight to 3 months), exposing them to rollover risk. Fundamentally, in addition to maturity mismatch, these financial institutions face currency mismatches, and may be forced to pay up for US dollars in times of market stress, or risk being forced to liquidate their US dollar assets.

This is observed in the behavior of the FX basis, which is the implied dollar interest rate (the cost of dollar funding) from the FX swap market. A negative basis means that borrowing dollars through FX swaps is more expensive than borrowing in the dollar money market. A negative basis represents a violation of covered interest parity (CIP), a condition in which the interest rate differential between any two currencies in the money markets should equal the differential between the forward and spot exchange rates. Otherwise, if not for the CIP equilibrium, there would be a riskless arbitrage where one could borrow US dollars cheaply in US money markets and lend in the FX market through a swap. CIP has been aptly described as “the closest thing to a physical law in international finance,” yet it has been consistently and continuously violated for almost a decade now.14

A negative FX basis is the result of hedging/funding demand and limits to arbitrage. The hedging/funding demand stems from banks with currency mismatches – “banking systems may be structurally short or long in specific currencies, given their core deposit base” (as explained earlier).15 Other hedging/funding demand comes from institutional investors’ hedging of USD asset portfolios, as well as non-financial firms’ opportunistic bond issuance.

Similarly, limits to arbitrage explains why the basis does not close, reflecting the fact that “balance sheet space is rented, not free” and that “in contrast to what the textbooks say, basis arbitrage involves market, credit, counterparty, and liquidity risks.”16 Thus, a large FX basis reflects a scarcity of dollar funding when balance sheet capacity is scarce (i.e. banks are risk averse and unable/unwilling to provision extra balance sheet space).

This highlights something very important and somewhat counterintuitive about the exchange value of the US dollar. US dollar appreciation (i.e. the increasing exchange value of the US dollar) is a reflection of the rising risks in the global financial and banking system caused by global banks pulling back from dollar intermediation, instead of as an indication of a general “flight to safety” during periods of market instability or as a result of the US economy outperforming the rest of the world and attracting capital inflows as a consequence.17

The mechanics of US dollar appreciation in this manner are analogous to a short squeeze. Foreign participants are synthetically short the dollar and must “roll” their funding every 1-3 months. As an example, Japanese life insurers hold around $1.5-2 trillion in foreign currency bonds (mostly dollar-denominated). The bulk of the FX hedging instruments used in such portfolios have short maturities (3 months or less). Thus, hedging a $2 trillion portfolio that is 80% dollar-denominated with a 60% hedge ratio using 3-month swaps would require $960 billion in new swaps every 3 months (“rolling” swaps) or $320 billion every month.

If one cannot come up with the $320 billion required to roll one’s swap or the price is suddenly higher due to elevated risk perceptions and an elevated FX basis as a result, one will be forced to either fire sale dollar-denominated assets (as a last resort) or somehow obtain more dollar funding, perhaps through the repo market, and pay up for the privilege of doing so (i.e. obtaining US treasuries, if one does not already have some, then repoing them out). Therefore, the pullback in dollar supply from global banks and relatively inelastic dollar demand result in a sharp appreciation in the dollar’s exchange value.

In summary, FX swaps are one of the main means of providing and receiving cross-border dollar funding. Since the full notional value of the contract is exchanged at the beginning and end of each transaction, FX swaps amount to a synthetic dollar loan collateralized by another currency. Therefore, the appreciation of the USD exchange rate relative to other currencies signals to us that dollar funding is becoming scarce and stresses are appearing in the wholesale interbank financing market. Furthermore, the demand for USD funding via FX swaps derives not only from foreign investor hedging of USD asset portfolios but also from the USD’s role as a vehicle currency for interbank transactions.

While FX swaps are one of the most important ways of providing and receiving cross-border dollar funding, they are not the only means of doing so. I will cover the bilateral repo portion of the wholesale funding market in my next research note.

https://warontherocks.com/2021/01/why-overseas-military-bases-continue-to-make-sense-for-the-united-states/

https://www.dw.com/en/china-navy-vs-us-navy/a-55347120

https://www.bis.org/publ/work828.pdf

https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs65.pdf

Jeremy Stein, “Dollar Funding and the Lending Behavior of Global Banks,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2015), 1241–1281.

https://voxeu.org/article/foreign-exchange-swaps-hidden-debt-lurking-vulnerability

BIS Committee on the Global Financial System no. 65 “US Dollar Funding: An International Perspective” June 2020.

Jeremy Stein, “Dollar Funding and the Lending Behavior of Global Banks,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2015), 1241–1281.

https://blogs.imf.org/2018/06/12/an-imbalance-in-global-banks-dollar-funding/

IMF Global Financial Stability Report 2019 Chapter 5 “Banks’ Dollar Funding: A Source of Financial Vulnerability.”

https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1912f.htm

Claudio Borio, “FX Swaps and Forwards: Missing Global Debt?,” Bank for International Settlements Quarterly Review, September 2017.

https://voxeu.org/article/foreign-exchange-swaps-hidden-debt-lurking-vulnerability

https://voxeu.org/article/bye-bye-covered-interest-parity

Ibid.

Ibid.

Stefan Avdjiev, Egemen Eren, and Patrick McGuire, “Dollar Funding Costs during the Covid-19 Crisis through the Lens of the FX Swap Market,” Bank for International Settlements Bulletin No. 1, April 1, 2020.

by dollar asset, do you mean a dollar-equivalent asset which can be converted into dollars readily, like U.S. Treasury bills, certificates of deposit etc?

dear maroon macro, can you please explain what is a "dollar asset"? I am tryig to read all your postings but sometimes I cannot cut through the jargon...

I know what a dollar is, but I do not know what a "dollar asset" is..