On February 22, 2022, the United States imposed its first tranche of economic sanctions against Russia, after Vladimir Putin recognized two regions of Ukraine as independent states and launched a “special military operation” that has turned into a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

On February 24, 2022, the United States, with the support of its allies and partners around the world, imposed increasingly severe economic sanctions against Russia.

In addition to these tranches of economic sanctions against Russia, a wave of both official sanctions and unofficial self-sanctions has also been levied against Russian oligarchs, Russian banks, and the Russian government.

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I am going to continue my coverage of the Russia-Ukraine crisis, this time attempting to analyze and assess the most significant economic restrictions against Russia, as well as providing overview and context as to why these economic restrictions matter, thus allowing a better understanding of the affected systems. While similar levels of restrictions have been levied against countries like Iran and Venezuela before, no such level of restrictions has ever been levied against a country as connected to the global economy as Russia.

Here’s a summary of the most important steps that have been taken:

Select Russian banks have been disconnected from SWIFT (as of March 12, 2022).1

Dollar-denominated and Euro-denominated assets of the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) have been frozen.

Sberbank’s connection to the US financial system has been frozen by preventing it from accessing its correspondent and payable-through accounts.

Full blocking sanctions have been imposed on several of the largest Russian financial institutions, including VTB, VEB, and Promsvyazbank. This freezes any and all of their assets that involve the US financial system, and also prohibits Americans from dealing with them.

The Russian government, Russian sovereign wealth funds, the Central Bank of Russia (CBR), and more than a dozen other Russian state-owned entities and enterprises have been cut off from US financing. This means that the Kremlin can no longer raise money from the US and Europe and that the Kremlin’s new debt can no longer trade in US and European financial markets.

Personal sanctions have been imposed on a group of Russian elites and their family members. In addition, a joint task force has also been commissioned to hunt down the physical assets of sanctioned Russian entities, enterprises, and oligarchs.

What is “SWIFT” and Why Does “De-SWIFTing” Matter?

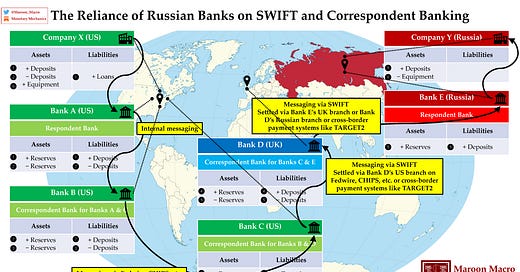

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), founded in 1973, is a cooperative organization that is owned by over 2,400 financial institutions, governed by an elected board of 25 directors, and headquartered in Belgium. SWIFT is currently the primary international financial messaging service for cross-border payments sent and received between financial institutions in different countries. Today, at least 11,500 financial institutions from 200 different countries utilize and depend on SWIFT’s messaging service for cross-border payments.2

SWIFT transmits $140 trillion in payments every year. In contrast, China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), which both utilizes and competes with SWIFT, combined with Russia’s System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS), which is the Russian equivalent of SWIFT, together facilitate transactions worth less than 0.5% of SWIFT’s volume/value.3

Over the past several decades, the growth of international trade in goods and services has naturally led to a growth in the volume and value of cross-border payments. International financial messaging systems play a pivotal part in the global financial infrastructure. These systems enable financial institutions to send and receive financial messages, as they contain and carry important information about the transactions (e.g. the sender, the recipient, the type of transaction, and the amount of transaction), so that financial institutions can verify the legitimacy of the transactions before the transactions are settled and made available/accessible in the accounts of the recipients.

An international transfer of funds typically involves both the sender’s and the recipient’s banks, a clearing and settlement institution, and an electronic financial message with instructions for the transfer. National payment systems, such as the Federal Reserve’s Fedwire System, have their own clearing, settlement, and financial messaging services, but their services are limited to their countries’ domestic financial institutions. On the other hand, SWIFT provides international financial messaging services, but does not provide clearing and settlement services.

China and Russia have already instituted their own financial messaging systems (CIPS for China and SPFS for Russia), and intend to link their two systems together, possibly along with India’s proposed system to support cross-border payments in its own currency.

Because SWIFT is incorporated in Belgium, the United States does not actually have the direct authority and ability to forbid SWIFT from processing financial messages to and from institutions subject to sanctions by the US government. In the case of Iran, the US government approved sanctions against the international financial messaging systems themselves, sanctions that would be put in place unless they removed certain Iranian financial institutions from their systems. In the end, SWIFT quickly removed the Iranian financial institutions in question.

What Part Does SWIFT Play in Cross-Border Financial Transactions?

As I have already mentioned above, an international transfer of funds typically involves both the sender’s and the recipient’s banks, a clearing and settlement institution, and an electronic financial message with instructions for the transfer. The clearing and settlement institution, which may or may not also relay financial messages, is responsible for transferring the funds and processing the transaction between the banks after the details of the transaction are verified.

In theory, for a simple cross-border payment, the sender initiates a payment with the sender’s bank, then the sender’s bank relays a financial message to the recipient’s bank with instructions for the transfer. Then, the recipient’s bank verifies the legitimacy of the payment. Lastly, a clearing and settlement institution clears and settles the payment.

In reality, however, the processing of a cross-border payment will likely involve multiple banks, particularly if the sender’s and the recipient’s banks do not have a correspondent banking relationship.