In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I am going to formally outline a trade idea that I have been thinking about for the past few months since the recent reflationary impulse has stopped dead in its tracks. I first formed my thesis before news about Evergrande broke, and although my thesis is not contingent on a major Chinese credit crisis, I still believe that increased risk-off sentiment resulting from the Evergrande drama has perhaps increased the likelihood, as well as accelerated the timeline, of a CNY devaluation.

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I am going to avoid talking too much about Evergrande, as there are many others who are better informed about the specifics of the Evergrande situation than I am. However, I will mention it only to opine on what it might mean for risk sentiment, funding/financing and liquidity pressure in China, and, as a consequence, the ability of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to manage the CNY/USD exchange rate.

Many of the concepts that I will discuss in this issue of Monetary Mechanics are derived from concepts that I have already discussed in detail in Issue #18 (on the determination of foreign exchange rates). Please read or review that if you want/need more information about that before we move forward.

Context

Since around 2014, China’s economy has become one of the marginal drivers of global economic growth, as well as the marginal recipient of global capital flows. One of the main reasons behind this phenomenon is that, post-GFC and post-European sovereign debt crisis, people thought that the developed markets (i.e. the US, the UK, and Europe) would have difficulties growing for the next several years while they tried to get their houses in order (e.g. pass new regulations to restructure their banking systems). With the banking systems being forced to delever in the process, people thought that the combination of excessive debt and a poor demographic outlook would cause the developed market economies to suffer serious setbacks.1

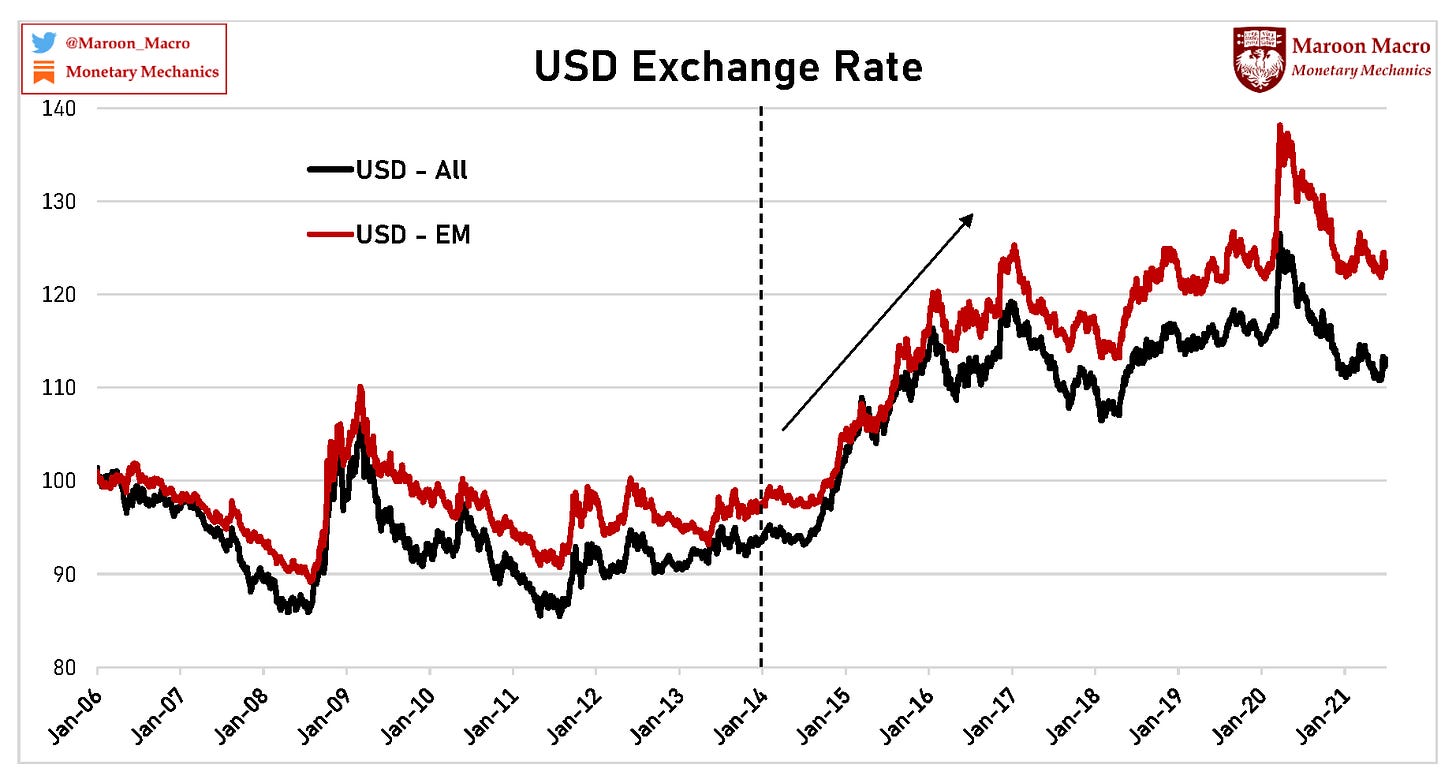

The figure above shows the broad trade-weighted US Dollar index against loans and total credit to emerging market economies. The figure above paints a striking and extremely convincing picture that emerged in the post-GFC era – the value of the US Dollar rises during periods of weak credit growth. Why is this happening? One must remember that the value of the US Dollar is determined by the availability/accessibility of US Dollar credit. Hence, a falling of the value of the US Dollar is synonymous with and the result of a global expansion of US Dollar credit.

Consequently, the global economy has experienced growth spurts and slowdowns that were roughly in line with China’s credit impulse (with only brief exceptions in 2011 and 2019 when Chinese credit stimulus tried to counteract global deflationary forces).

China Credit Impulse vs. Global Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI)

This has resulted in a very close relationship between the CNY/USD exchange rates and what I refer to as the “global reflation trade,” which is basically just a shorthand for a risk-on environment in which global dealer banks are more than happy to extend credit for any and all sorts of purposes, global economic growth accelerates, and inflation pressures start to emerge (or people start to worry about inflation pressures).

The figure below shows that these reflationary periods, proxied by the 10-year US Treasury yield, tend to coincide with periods of CNY strengthening. This happens because the easing of global credit conditions causes more and more dollars to flow throughout the global economy and into China, strengthening CNY. Thus, a tightening of global credit conditions causes dollars to dry up, weakening CNY.

Global Supply and Value Chains and China’s Trade Dependency

China is extremely externally dependent on gross trade flows (i.e. importing, value-adding, exporting). China is the largest trading nation on the planet and either the largest or the second largest trading partner of virtually every single country today. Here are some quick facts about China:

China has approximately $4T worth of gross trade flows each year ($1.5T imports and $2.5T exports).2

Gross trade (imports and exports) is approximately 35-40% of China’s total GDP, making China one of the most (if not the most) active trading nations on the planet (both in absolute terms and in relative terms, relative to the size of its GDP).3

Of these gross trade flows, a whopping 70-80% are dollar denominated while only 20-30% are yuan denominated.4

Manufacturing and importing/exporting are very finance intensive businesses. Unless outflows perfectly match inflows and payments seamlessly occur on a T+0 basis (i.e. same day payment settlement), businesses must depend on various forms of short-term credit in order to facilitate the efficient flow of goods and services.

The provision of this short-term credit is done by banks at both local and international levels. On the one hand, importers generally need dollars to buy goods from international markets, but often sell goods into local markets for local currency. Naturally, importers have a constant demand for dollars and supply of local currency. On the other hand, exporters generally need local currency to buy factors of production from local markets, but often sell goods into international markets for dollars. Naturally, exporters have a constant demand for local currency and supply of dollars.

While China has been trying to decrease its dependence on the dollar, its efforts have not been successful so far, evidenced by the large percentage of gross trade flows into and out of China that is still dollar denominated.

These imbalances tend to be obscured on a net basis, because the dollar short position of the importers is counterbalanced by the yuan short position of the exporters in such a way that the overall currency mismatch for the entire country seems small to the casual observer (or it is believed that there is a perfect and smooth dollar flow to importers from exporters).

However, we have witnessed an example of this fallacy before, in Issue #18 of Monetary Mechanics, in which European banks acquired dollar denominated assets using US MMF wholesale funding and built up large gross positions that were eclipsed by a deceptively low and stable net exposure.

Cross-Border Bank Lending (in US Dollars)

In today’s globalized world, where supply and value chains have become increasingly complex, there is an interlocking system of payables, receivables, and credit that acts as the glue that holds the world economy together. Because funding needs grow at the square of the length of supply and value chains, financing needs grow rapidly and remain high.5 The value of the US Dollar not only has immediate implications for financial market participants, but is also intimately tied to the needs of the real economy, acting as the lynchpin that holds the financial and real economies together.

What this means for China, as an extremely trade-dependent economy, is that its ability to function effectively hinges on its ability to source and continually attain dollar funding/financing.

There is no possible way for us to know how big China’s dollar short position precisely is. However, we can estimate its size based on a couple of facts: we know approximately how dependent China’s economy is on global trade, we know approximately how much of China’s trade flows are USD denominated, and we know that about 50-60% of China’s FX reserves are USD denominated.

In addition, we also know that ever since the fiasco in which China lost $1T of FX reserves back in 2016, China has been using its state-owned banks to intervene in the FX market on the People’s Bank of China’s behalf to stabilize the currency in a way that will not show up on bank balance sheets.6 However, this tactic can only last so long – the downside of conducting these transactions is that they generate a future demand for dollars, a demand that will likely coincide with a decrease in USD liquidity, which will further compound China’s dollar short position problems.

The global reflation trade has been petering out since March (there are too many indicators to fully flesh out here: UST yields, inflation, inflation expectations, weak global economic growth, etc.). Then, this Evergrande story started developing in the last month or two. While it remains to be seen what will eventually happen to the Chinese real estate market, as well as China’s economy as a whole, this Evergrande story is definitely not positive for global risk perceptions. What this means is that global banks will begin to pull back and shrink risk exposures on their balance sheets around the margins, a process that already began with Archegos back in March.

Dollar bonds are the canary in the coal mine. While we cannot directly observe the Chinese state-owned banks’ FX swap/forward activities, we can, however, indirectly observe the Chinese state-owned banks’ increasingly expensive access to USD funding/financing. Because 50-65% of the People’s Bank of China’s assets are FX reserves, and most of those FX reserves are dollar denominated, offshore USD illiquidity puts significant pressures on domestic monetary conditions, consequently cascading into tightening domestic credit conditions (both USD and RMB) throughout the entire Chinese economy.

This is the reason why there has been such desperation from Chinese officials to increase credit and M2 recently. A tightening of offshore monetary conditions puts pressures on the assets side of the People’s Bank of China’s balance sheet (i.e. FX reserves) and the FX assets of the Chinese banking system as a whole. This is because a tightening of offshore monetary conditions is equivalent to financial market participants taking USD out of China (i.e. selling CNY and buying USD) or the tapering of USD credit to Chinese banks and businesses (which is, again, taking USD out of China). Thus, the People’s Bank of China (or the Chinese banking system at the behest of the People’s Bank of China) must absorb these pressures, buying CNY and selling USD itself to offset the selling of CNY and the buying of USD done by others, to maintain the stability of the CNY/USD exchange rate.

This mechanically decreases the assets side of the People’s Bank of China’s balance sheet (i.e. FX reserves), which decreases its liabilities side as well, due to the rules of double-entry bookkeeping. Since the liabilities side of the People’s Bank of China’s balance sheet (i.e. bank reserves and physical currency) forms the foundation of China’s monetary system, selling FX reserves is essentially a form of quantitative tightening, amounting to a tightening of domestic monetary conditions.

If the bank-centered endogenous monetary system can make up for the reduction in bank reserves, the entire Chinese economy would be sheltered from the storm. However, nothing ever works 1:1 in this world, so once global deflation sets in, the entire Chinese economy would be as helpless as a tiny sailboat struggling on a stormy sea.

Here is a timeline of recent events that narratively shows the escalating pressures on the entire Chinese economy transmitted via tight USD liquidity conditions:

September 24:

“China Drafts New Rules for Banks’ Overseas Yuan Lending to Boost Yuan Use”

September 8:

“China’s Central Bank Says Liquidity Is Ample and Balanced” — The PBOC has adequate tools to smooth out periodic fluctuations in liquidity… The PBOC is fully capable of maintaining reasonably abundant liquidity.

“Ray Dalio Says China Opportunities Can’t Be Neglected”

“BlackRock initiates China government bonds with overweight”

“Global Private Banks Stop Accepting Fantasia Bonds as Collateral”

September 6:

“CHINA’S MAJOR STATE-OWNED BANKS SEEN BUYING U.S. DOLLARS IN ONSHORE SPOT MARKET LATE FRIDAY – SOURCES”

September 3:

“China to draw foreign investors into commodities futures trading” — China will launch more futures contracts, including a shipping futures contract, and accelerate efforts to bring in more overseas investors to trade in its futures market, the State Council, or cabinet, said on Friday. China will also establish an international, yuan-denominated commodity futures market, it said in a statement on promoting trade and investment in its free-trade zones.

“#Evergrande bonds deemed worthless in #Shanghai Exch. Repo deals and deleted from #Shenzhen Exch. Repo deals – BBG”

September 2:

“CHINA IS DEDICATED TO OPENING UP ITS ECONOMY AND WELCOMES GLOBAL INVESTMENT”

August 30:

“EXCLUSIVE China’s FX regulator surveyed banks, companies on yuan risk – sources” — China’s currency regulator has been conducting a rare survey of banks and companies to ask about their risk management processes and ability to handle volatility in the yuan, three banking and policy sources told Reuters. The State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) surveyed “how companies in different sectors managed their FX exposure and how they used hedging tools,” said one of the sources, who was directly involved in the survey.

August 27:

“PBOC Signals Reserve Ratio Cut to Boost Rural Finance” — The People’s Bank of China said it will use monetary policy tools including the reserve ratio, and relending and rediscounting measures for rural development, according to a statement Thursday. That fueled speculation of a targeted RRR cut, possibly as soon as Friday.

August 26:

“Amid ‘Uneven’ Recovery, PBOC Urges Banks To Lend More”

August 24:

“#PBOC said in a recent meeting that “more efforts are needed to keep steady #credit growth.” Many believe that indicates it’s concerned about weak credit demand as economic recovery loses momentum and is likely to take actions to loose credit condition.”

March 2021:

“Chinese state banks seen using FX swaps to absorb dollars, sources say” — The sources said the bank was seen conducting sell-buy swaps in the dollar-yuan pair, alongside its purchases of dollars from exporters and other corporate clients. They suspected the swaps were aimed at getting around monthly quotas on the amount of foreign currency banks can buy, by transferring some of those dollar purchases onto their forward books. “The big bank has been buying quite huge amounts of one-year dollars in the swap market,” said one source, speaking on condition of anonymity.

October 2020:

“Exclusive: Chinese banks seen swapping dollars for yuan in forwards to curb gains – traders” — Those operations in the onshore currency swap market have caused the value of the yuan to fall in the forwards market, tamping expectations that it will appreciate further and simultaneously making it more expensive for investors to borrow yuan. Two other traders told Reuters they saw big state banks buying dollars in the onshore spot market during late night trading sessions to effectively prevent the yuan from strengthening too fast.

Recommendation

My recommendation is to buy 10-delta USD/CNH calls for March 2022.

Within the last month, everyone and their mothers have been trying to encourage investors to move back into China (e.g. Ray Dalio, BlackRock, etc.).

We know that China has cut its reserve requirement ratio (RRR) earlier this year, and is attempting to boost credit and M2 growth, which it also did back in 2015-2016, this time with a “common prosperity” campaign (the Chinese government’s slogan for narrowing China’s socioeconomic chasms). We understand the way central bank accounting works, and that 50-65% of the People’s Bank of China’s balance sheet are FX reserves, a large portion of which are dollar denominated. We understand that global supply and value chains are very dependent on short-term credit, a very large portion of which is dollar denominated. We understand that China is currently the largest and most active trading nation on the planet, with ~$4T worth of gross trade flows every year, only a negligible portion of which is yuan denominated. We understand the way FX rates and flows work, and that the global reflation trade started rolling over 6 months ago. China’s economic data also started falling off a cliff 1-2 months ago, and recent (rather negative) news headlines and stories regarding Evergrande and Huarong are going to scare dollar flows away from China.

Consequently, all of the above demonstrate that things are beginning to look bad for CNY. If you can, double-check with your sources at the Bank of China and focus on the timing of their FX swaps/forwards. We can see that the Chinese state-owned banks have forwards rolling off between 1-6 months from now (i.e. there will be a very large demand for dollars over the next 1-6 months). My Chinese friend sent me a recording of a recent speech that a People’s Bank of China governor gave at a Chinese business school, and what he says further confirms my views.

The mainstream financial market, running with the “money printing leading to too much liquidity” narrative, believes that there are “too many dollars” washing around within the financial system. Zoltan Pozsar of Credit Suisse went on the Odd Lots podcast earlier this month, and what he says confirms the same. However, one can argue that he is not an expert on FX, as he focuses mostly on US money markets. Moreover, one can argue that he is not as good at estimating the direction as he is at explaining the plumbing, as he has been wrong on specific market calls before.

One can argue that China’s (lagged) balance of payments data confirms that the Chinese banking system accumulated significant USD assets up through Q1-Q2, signifying that it has a large excess supply of USD assets. However, balance of payments data does not account for off-balance sheet activity. Moreover, the Q2 balance of payments data neither illustrates the petering out of the global reflation trade since March-April, nor illustrates the global reflation trade taking a hard turn in the downward direction in June-July.

One can also argue that the People’s Bank of China has a large enough stockpile of USTs that it can use to defend the CNY. However, it already lost $1T doing that back in 2016 and it has publicly stated that it does not want to do that again, so the People’s Bank of China has been forcing the Chinese state-owned banks to do its dirty work for it instead through the FX swaps/forwards market. In a last-ditch attempt to defend the CNY, however, the People’s Bank of China can go to the Federal Reserve to repo its USTs, to try to weather temporary dollar shortages, as the Federal Reserve just made the Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) repo facility permanent a month ago, perhaps in an intentional move.

The information provided herein is for informational and educational purposes only. It should not be considered financial advice. You should consult with a financial professional or other qualified professional to determine what may be best for your individual needs. Monetary Mechanics does not make any guarantee or other promise that any results may be obtained from using the content herein. No one should make any investment decision without first consulting his or her own financial advisor and conducting his or her own research and due diligence. To the maximum extent permitted by law, Monetary Mechanics disclaims any and all liability in the event any information, commentary, analysis, opinions, advice and/or recommendations prove to be inaccurate, incomplete, unreliable or result in any investment or other losses. Content contained or made available herein is not intended to and does not constitute investment advice and your use of the information or materials contained is at your own risk.

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2014-11-18/the-burden-of-a-stronger-dollar

https://oec.world/en/profile/country/chn#monthly-trade-exports-imports

https://santandertrade.com/en/portal/analyse-markets/china/foreign-trade-in-figures

https://www.realvision.com/shows/the-expert-view/videos/dollar-liquidity-the-end-game-for-china

https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp170625b_slides.pdf

https://www.afr.com/markets/currencies/china-is-intervening-in-currency-markets-by-stealth-20200920-p55xdp

Note: I disagree with some of the premises in this article and cite it only to highlight its coverage of the Chinese state-owned banks’ intervention in the FX market on the People’s Bank of China’s behalf.

Great trade

Any recommendations for books on Eurodollar system?