Issue #49: Quantitative Tightening: The Federal Reserve’s Portfolio of Mortgage-Backed Securities

In the previous issue of Monetary Mechanics, I offered a high-level overview of the various scenarios that could occur as the Federal Reserve begins to unwind its balance sheet.

In addition, I also demonstrated how different scenarios would have different effects on the primary liabilities of the Federal Reserve (reserve balances, the overnight reverse repo facility, and the Treasury General Account).

Specifically, I demonstrated that the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet decreases when the Treasury repays the Federal Reserve while securities mature in the Federal Reserve’s System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio. This sequence of steps results in decreases in the net sizes of both the Federal Reserve’s and the Treasury’s balance sheets. However, I also demonstrated that the decrease in the Treasury General Account (TGA), the Treasury’s cash balance, is not sustainable, since the Treasury requires an adequate surplus of cash to fund/finance day-to-day government functions.

Since the implementation of fiscal policy by the Treasury and the implementation of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve are independent from one another, the Treasury must take these maturing securities into account when it decides its quarterly refunding schedule to ensure that it has enough cash on hand. Therefore, we can conclude that the Treasury would issue new securities (“roll over” its maturing debt) to the private sector to replace these maturing securities.

Ultimately, who purchases those securities, as well as how they purchase them, causes a chain reaction of financial transactions that control how the balance sheets of the Federal Reserve, the banking system, the money market fund industry, and the rest of the private sector change in reaction/response to quantitative tightening.

In the previous issue of Monetary Mechanics, there were a couple of complications that I acknowledged but did not answer completely.

What is the Federal Reserve going to do with its rather large portfolio of off-the-run mortgage-backed securities (MBS)?

How is the cadence of bills runoff vs. coupons runoff going to affect money markets?

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I am going to attempt to answer the first question, as well as offer some big picture takeaways along the way about the direct effects of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet operations on not only money markets but also the broader financial system.

The Federal Reserve’s Portfolio of Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

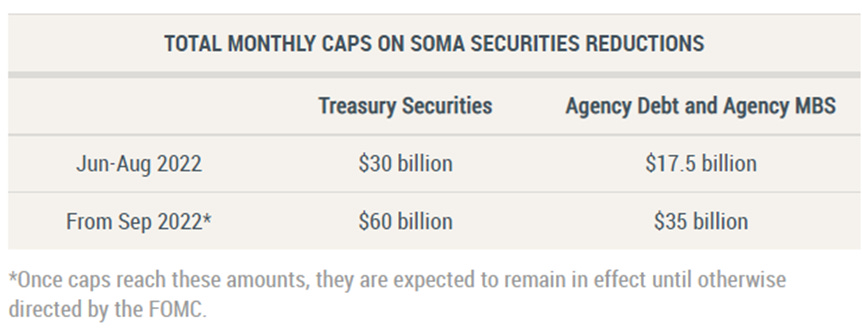

The previous issue of Monetary Mechanics ended with these two figures, which are projections of balance sheet runoffs of bills, coupons, and mortgage-backed securities, given the Federal Reserve’s confirmed runoff pace of $60 billion/month of US Treasury securities and $35 billion/month of mortgage-backed securities.

There are important differences in these two figures. The figure on the left shows the monthly cap on mortgage-backed securities rolloffs plotted against the projected paydowns of the mortgage-backed securities in the Federal Reserve’s SOMA portfolio. The key word here is “projected.” The figure below shows that, if Wells Fargo’s projections are reasonably accurate, the Federal Reserve will fall far short of its proposed monthly cap on mortgage-backed securities reductions.