Since the Federal Reserve is on the brink of beginning its quantitative tightening (QT) program, beginning June 1, I thought that I should dedicate an issue of Monetary Mechanics to the mechanics of quantitative tightening, just like I did for the mechanics of quantitative easing before back in Issue #7 of Monetary Mechanics.

Unlike the last time that the Federal Reserve tried to decrease the size of its balance sheet, there are a few significant and substantially different points about this time around:

The Federal Reserve’s reverse repo (RRP) facility is at all-time highs of around $2 trillion.

The Federal Reserve’s System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio has sizable holdings of mortgage-backed securities, which, if left to run off naturally, may cause complications.

The standing repo facility (SRF) is now a permanent fixture of markets, theoretically functioning as a backstop to prevent something like the September 2019 repo spike from happening again.

The US Treasury market has grown from approximately $16 trillion to approximately $22.5 trillion in size, a growth of about 40% since September 2019.

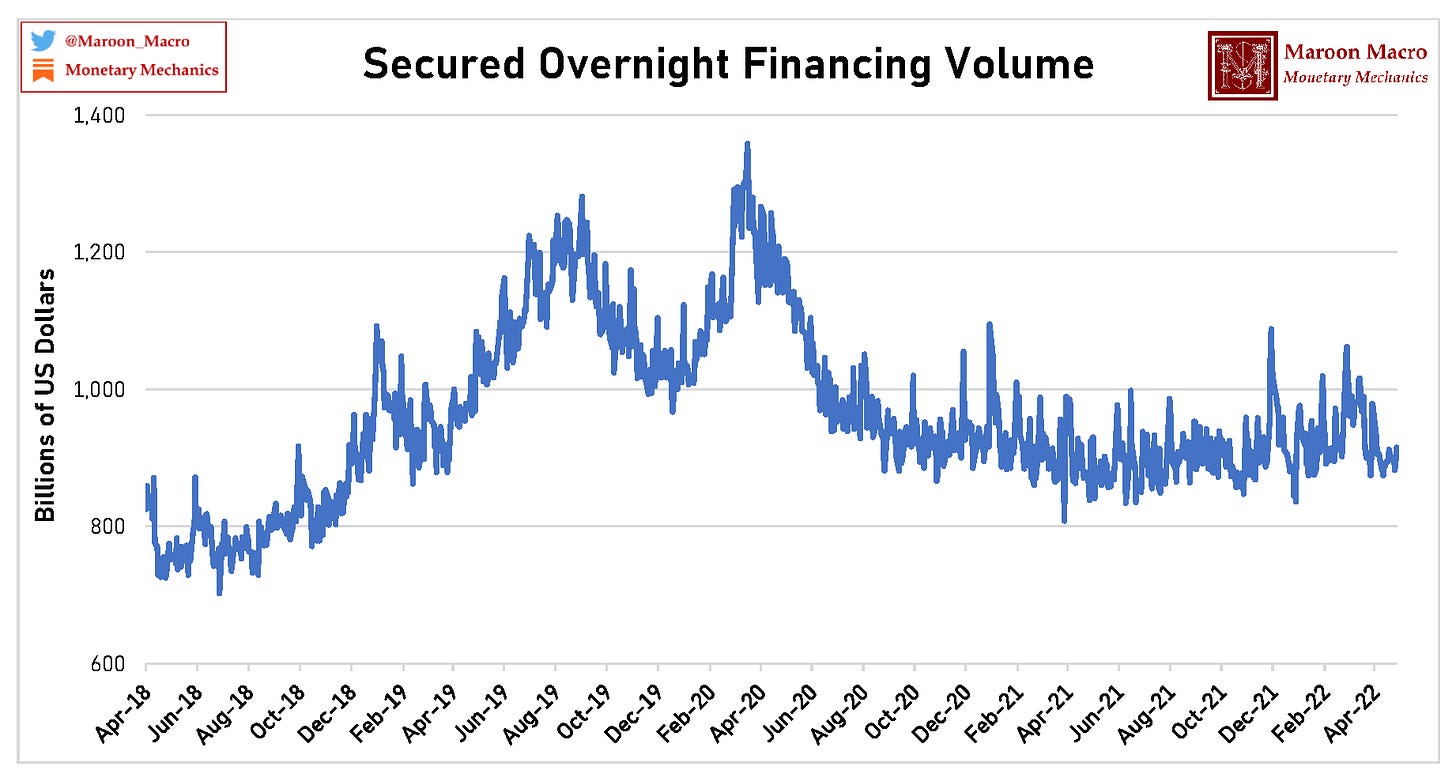

The US Treasury repo market, meanwhile, has actually shrank from approximately $1,250 billion in September 2019 to approximately $850 billion today in size, as measured by Secured Overnight Financing (SOFR) volumes.

All of these things are additional wrinkles that we must bear in mind when we think about the Federal Reserve’s quantitative tightening program this time around. However, before we begin, let’s review some basics, starting with a review of quantitative easing.

A Review of Quantitative Easing (QE)

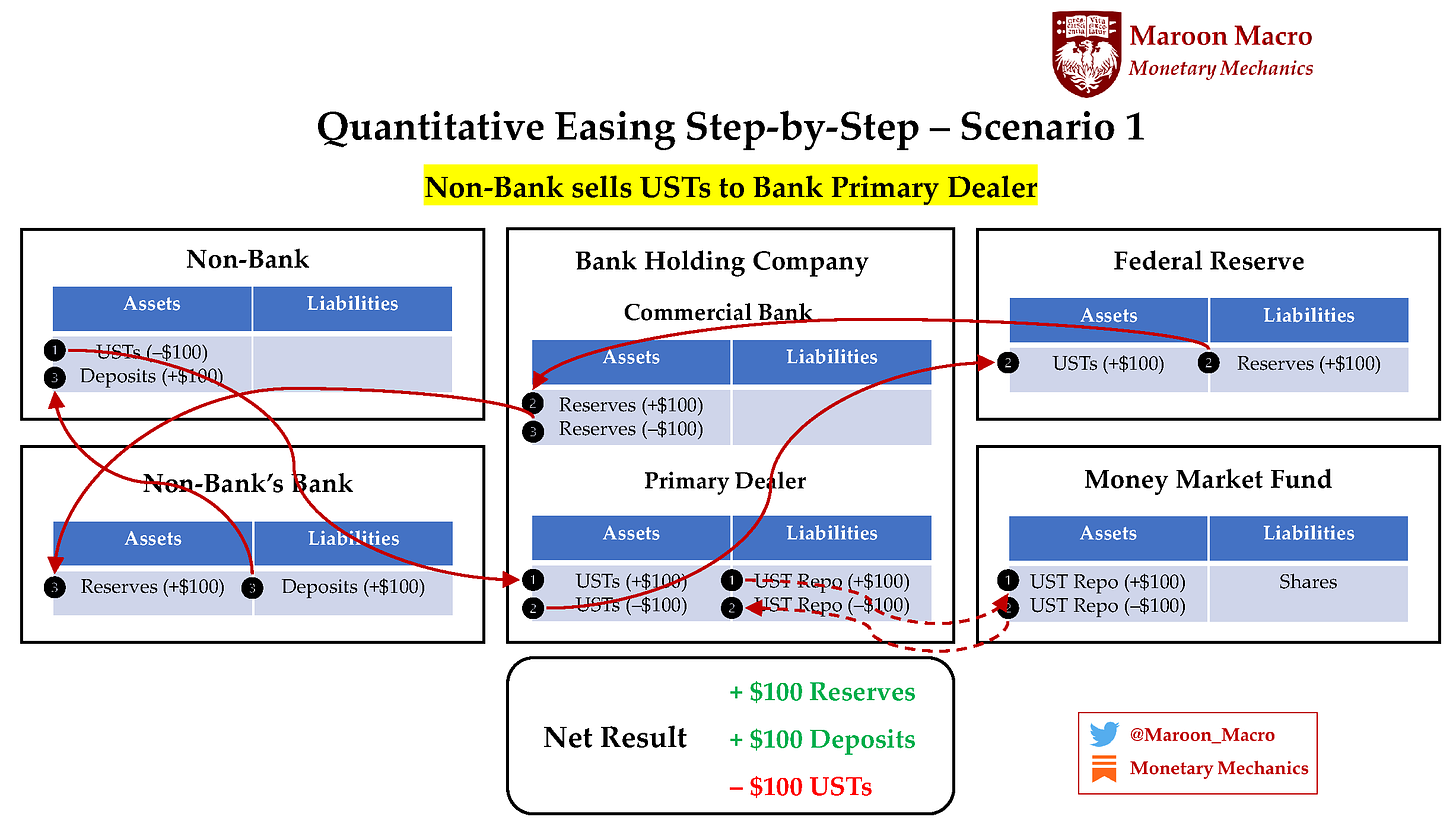

Quantitative easing happens when the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) purchases securities from primary dealers who are supposed to solicit bids from clients/customers.

When the Federal Reserve purchases securities from a bank, reserve balances increase in equal proportion to the value of the securities purchased – so the net impact on the banking sector’s balance sheet is neutral.

When the Federal Reserve purchases securities from a nonbank (typically some type of mutual fund, pension fund, or institutional investor), reserve balances and bank deposits are created and increase in equal proportion to the value of the securities purchased (e.g. $100 of quantitative easing would create $100 of reserve balances and $100 of bank deposits) – so the net impact is an increase in the banking sector’s balance sheet.

Quantitative easing is how the Federal Reserve increases the size of its balance sheet.

Since fixed income securities have expiration dates, the Federal Reserve must constantly reinvest the proceeds of maturing securities into newly issued securities in the primary market, to maintain the size of its balance sheet.

An Explanation of Quantitative Tightening (QT)

Quantitative tightening, which we will assume does not include outright sales of mortgage-backed securities for the moment, works in a similar way.