Issue #46: The Russia-Ukraine Crisis – Could China Be a Lifeline for Russia’s Banks?

In the previous issue of Monetary Mechanics, I provided an overview of the economic sanctions that have been placed upon Russia by the West, focusing primarily on the ramifications of the exclusion of select Russian financial institutions from the rest of the global cross-border payments infrastructure, through the ejection of these Russian financial institutions from SWIFT and the dollar-denominated correspondent banking network.

In this issue of Monetary Mechanics, I am going to talk about Russian and Chinese financial plumbing, proposing a few possibilities where China could be able to assist Russia with access to international goods markets and, much more importantly, with access to payment processing.

I would like to begin by saying that I am not an expert in Russian and Chinese financial plumbing. However, this topic was recently brought to my mind by a friend, so I thought I would treat it as an interesting and timely thought experiment to fully flesh out here.

How Could China Help Russia’s Banks?

There are a few ways that China could help Russia’s banks in this situation.

First, we could consider the direct connections between the two countries’ central banks, both of which do not need to use SWIFT messages to make transactions.1 Russia may have as much as $140 billion total in yuan-denominated assets, consisting of approximately $80 billion held by the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) with the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), which is approximately 13% of the CBR’s total FX reserve stockpile, and another $60 billion held by the National Wealth Fund (NWF).2 Russia also has a $150 billion swap line agreement with China.

Russia can use these funds to finance imports from China in yuan in the event that other trade finance routes in dollars and euros are blocked. However, this trade will largely, if not completely, remain in yuan, which will limit what Russia can purchase from China. What Russia is really short of are dollars and euros (not yuan).

The Chinese government is currently being careful to not incur US secondary sanctions against itself, and at least two of the largest Chinese state-owned banks have already restricted funding/financing for purchases of Russian commodities, in spite of China’s and Russia’s outward and ostensible friendship. Primary sanctions are already used to target Russian financial institutions and American firms that interact with them. Secondary sanctions, while not yet used, would target third parties outside of the United States that interact with Russian financial institutions and firms, even if those interactions are technically allowed according to local law.

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s offshore units have stopped issuing dollar-denominated letters of credit for purchases of physical Russian commodities ready for export. However, yuan-denominated letters of credit are still available/accessible for some clients/customers, subject to approval from senior leadership. In addition, Bank of China has also curbed funding/financing for purchases of Russian commodities based on its own risk assessment. However, Bank of China has not yet received explicit guidance regarding the Russia-Ukraine crisis from the Chinese government.3

Moreover, allowing Russia to sell yuan-denominated assets to raise dollars and euros could mean attracting unwanted scrutiny, and going beyond what the Chinese government is willing to do.

The Chinese Financial and Banking System

What could a possible Russia-China collaboration look like, aside from the aforementioned methods? There are several financial and banking networks that China has spent a significant amount of time and energy shaping, networks that could come in handy in this specific situation.

The Importance of China as a Counterparty

The Chinese government may have stated on March 2, 2022, that China would not join Western economic sanctions, but most big Chinese banks will almost certainly adhere to them, especially those that have legal entities in the United States and those that interact the most with the Western financial and banking system. These large Chinese financial institutions, which facilitate the bulk of trade finance between Russia and China, are unlikely to continue doing dollar-denominated business with Russia, for fear of getting blocked from dollar clearing. For these large Chinese financial institutions, maintaining full and unfettered access to global financial markets is likely a top priority and something that is not worth risking/losing in the long run.

UnionPay, China’s state-owned bank card firm, is another powerful financial and banking network that is set to significantly expand its market share in the wake of the exits of Visa and Mastercard. UnionPay already has a presence in Russia, and several Russian banks have already announced that they will move to UnionPay.4 However, this move will not be an easy one to make. UnionPay’s network is still small within Russia, and many Russian banks have no existing relationship with UnionPay. Furthermore, UnionPay would predominately be useful for the processing of retail payments, as opposed to the processing of large-value wholesale payments.

One possible route for financial assistance may be small backchannel Chinese banks that are willing to dodge Western economic sanctions. The Chinese government has a long history of turning a blind eye to small backchannel Chinese banks that fund/finance trade with countries targeted by the United States and the United Nations. Some of these banks may be able to take the risk to support Russia, as they have less to lose even if they are hit by secondary sanctions. However, these banks are unable to give the large-scale support that is needed by Russia.

The Chinese Financial Payment and Messaging System

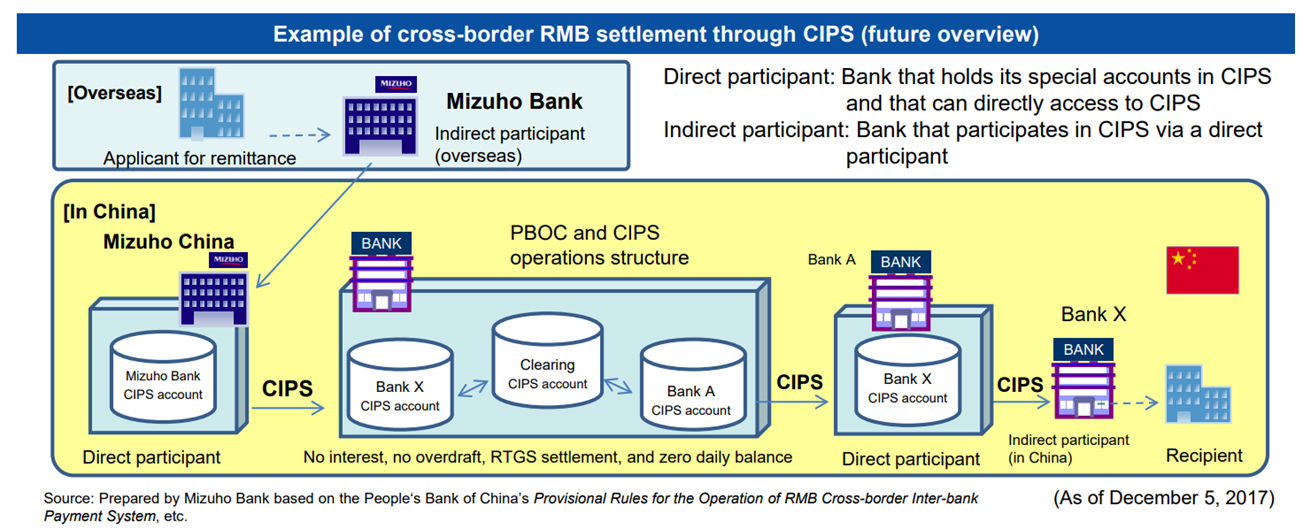

Now, let’s take a look at China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS).

CIPS was founded in October 2015 as a payment clearing and settlement system for transactions that use yuan. The system is owned by dozens of different shareholders, including Chinese financial institutions, firms, exchanges, and Western banks. The system is operated by CIPS Co. Ltd. in Shanghai, under the supervision of the Chinese central bank. Use of the system has steadily increased, with an average daily transaction value of ¥388.8 billion (approximately $61.3 billion) as of February 2022, which is about a 50% increase from just a year ago.5

In theory, it is tempting to think that CIPS can provide Russian banks a platform to conduct transactions without Western involvement/interference. In reality, however, CIPS cannot be of immediate help with circumventing Western economic sanctions for a number of reasons.